Duyen Chu, Qijun Zhou and Alistair Bogaars

Introduction

Employability and career services are an integral part of any UK higher education institution (HEI). Many factors can affect and shape the employability and career services of a university, including the constantly increasing demand of the job market, legal and professional requirements and institutional strategic priorities. In this blog, we develop and propose a framework for ensuring more inclusive and personalised student employability and career services. Materials for developing this blog derive from our broader Scholarship Excellence in Business Education (SEBE) and Connected Cities Research Group (CCRG)-funded project on student employability optimisation.

The need to ensure more inclusive and personalised student employability and career services

We need to ensure more inclusive and personalised student employability and career services because of the following reasons.

First, we need to better address the disparity between industry expectations and higher education (HE) provision and meet the demands of the job market. Globalisation, international mobility, rapid changes and increasing complexities in society, technology and the economy have set increasingly demanding requirements for HE, especially graduate employability (Bowman et al., 2017). HEIs have been under pressure to produce highly mobile and employable graduates who are required to be able to respond to the ever-changing needs of the contemporary workplace and contribute to the sustainability of economic development (Andrews and Higson, 2008; Small et al., 2018). As such, the onus is on the HE sector to present graduates, who are both work ready and have attained employability, to the labour market (Small et al., 2018).

HE providers have responded, somewhat haphazardly, by addressing employability skills development through embedding outcomes in core disciplinary content, devising ‘bolt-on’ programmes, introducing and capitalising on existing workplace learning programmes to develop these skills in an authentic work environment (Jackson, 2012). Despite the universities’ efforts, there is evidence suggesting that graduates moving from HE to the workplace are not meeting industry expectations and there is a continuing disparity between industry expectations and HE provision (Jackson, 2012; Matsouka and Mihail, 2016; Succi & Canovi, 2020).

Second, we need to fulfil the legal and professional requirements regarding inclusion in HE. Inclusion has been a focal issue in the HE sector over recent years (Zabeli et al., 2021). The UN 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has placed inclusion in HE within the human rights domain, requiring that development of an inclusive HE system is a legal obligation for ratifying countries, including the UK (Cui et al., 2019). Inclusion in UK HE has been driven by four main drivers: the government’s requirement for universities to charge the maximum tuition fee in order to demonstrate their commitment to widening access; the recognition of a degree awarding gap affecting BAME and other disadvantaged students; the introduction of the Equality Act 2010; and the revisions to the UK Professional Standards Framework for HE which emphasise the need for university teachers to demonstrate ‘respect for individual learners and diverse learning communities’ (Hockings et al., 2012).

Last but not least, we need to contribute to the implementation of institutional strategic priorities. Like any other integral part of a university, employability and career services can contribute to the delivery of institutional strategic priorities. For example, in the recently introduced new strategy ‘This is our time: strategy 2030’ of University of Greenwich, inclusivity and student success, including student personalised living and learning, university experience and employability, are at the heart of the strategy (University of Greenwich, 2022). Employability and career services at University of Greenwich can contribute to the implementation of these institutional strategic priorities.

A framework to ensure more inclusive and personalised employability and career services

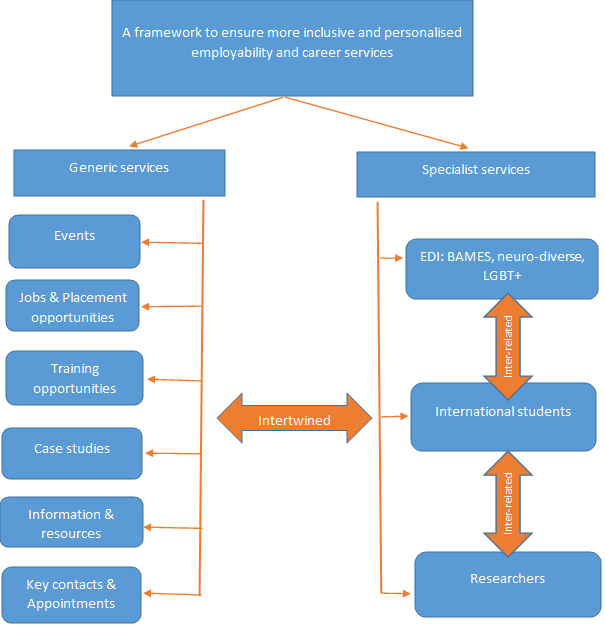

To develop a framework for ensuring more inclusive and personalised employability and career services, we follow the methodology of Farenga and Quinlan (2016) and look at the top ten best UK universities in terms of graduate outcomes in the Complete University Guide League Tables 2022. Our framework is presented in Figure 1.

In our framework, employability and career services are divided into two key parts: generic services and specialist services. Generic services are general services that have conventionally and typically been provided by universities. These services include employability and career events, job and placement opportunities, training opportunities, information and resources, key contacts and appointments. It is noticeable that the top universities tend to include successful case studies of students on their employability and career services websites, which enables students to see and relate to themselves more easily.

The second key part in our framework is specialist services. Specialist services are the more specialised employability and career services that are provided by some universities only. For example, University of Warwick and London School of Economics and Political Science pay particular attention to Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) while Durham University and University of Leeds particularly focus on international students. University of Bath provides specialist support for researchers.

Figure 1. A framework to ensure more inclusive and personalised student employability and career services

All these specialist services can help optimise support for students. More specialised services focusing on EDI can cater for more diverse groups of students in a Widening Participation university, especially BAME, neuro-diverse and LGBT+ students. Support for international students is a key element in the specialist services in our framework. Previously, international students were not typically included in the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) national survey on graduate outcomes which takes place 15 months after students finish their studies (HESA, 2022). However, the UK new graduate visa scheme allows international students to stay in the UK for up to 24 months after completing undergraduate and postgraduate studies or up to 36 months if they have a PhD or other doctoral qualification (Graduate Visa, 2022). This new visa scheme will have huge implications for the HESA survey on graduate outcomes and employability and career services provided by universities to international students. Postgraduate research students could be less a focus in conventional employability and career services, but they are still an integral part of the student population of a university. Therefore, employability and career services for researchers are an important element in our framework. Specialist support for EDI, international students and researchers are inter-related. For example, a student can belong to a BAME group as an international student doing a doctoral degree. The student can access all the specialist support in the framework.

Rather than being mutually exclusive, the generic and specialist services should be intertwined and correlated. Operationally, all students can access generic services and students with more specialised needs can be directed to relevant specialist services. Therefore, resources are inter-related, which means employability officers with specialist knowledge can easily extend their support from the more conventional generic services to the specialist services. As a result, there could be no significant increase in terms of resources when applying the new framework.

The employability and career services of many universities may have been covering some or most of these aspects. However, they might not have shown them explicitly. Our framework would be useful for them to design, develop and show what they do more explicitly, which can be more visible, appreciated and utilised by students.

Conclusion

The rapidly changing world and job market have created challenges for HEIs in supporting their graduates in terms of employability and career development. Employability and career services can also be influenced by legal and professional requirements and the strategic direction of a university. By studying the top ten UK universities in terms of graduate outcomes, we develop a framework to ensure more inclusive and personalised employability and career services. The framework consists of two intertwined parts: generic and specialist services. The framework would be useful for universities to design, develop and show what they do more explicitly and provide more benefit to students in terms of employability and career support, consequently addressing the broader challenges and requirements for HE.

References

Andrews, J. and Higson, H. (2008) ‘Graduate employability, “soft skills” versus “hard” business knowledge: a European study’, Higher Education in Europe, 33:4, 411‒422. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720802522627 (Accessed: 26 November 2021).

Bowman, D., McGann, M., Kimberley, H. and Biggs, S. (2017) ‘Rusty, invisible and threatening: ageing, capital and employability’, Work, Employment and Society. 2017;31(3):465-482. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016645732 (Accessed: 22 November 2021).

Cui, F., Cong, C., Qiaoxian, X. and Chang, X. (2019) ‘Equal participation of persons with disabilities in the development of disability policy on accessibility in China’, International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 65(5), pp. 319‒326. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1664842 (Accessed: 26 November 2021).

Farenga, S.A. and Quinlan, K.M. (2016) ‘Classifying university employability strategies: three case studies and implications for practice and research’, Journal of Education and Work, 29:7, 767‒787. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1064517 (Accessed: 26 March 2022).

Graduate Visa (2022) Graduate Visa Scheme. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/graduate-visa (Accessed: 26 March 2022).

HESA (2022) About the survey: Graduate Outcomes. Available at: https://www.graduateoutcomes.ac.uk/about-survey (Accessed: 26 March 2022).

Hockings, C., Brett, P. and Terentjevs, M. (2012) ‘Making a difference ‒ inclusive learning and teaching in higher education through open educational resources’, Distance Education, 33(2), pp. 237‒252. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.692066 (Accessed: 26 November 2021).

Jackson, D. (2012) ‘Business undergraduates’ perceptions of their capabilities in employability skills: implications for industry and higher education’, Industry & Higher Education, 26(5) October 2012, pp. 345–356. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5367/ihe.2012.0117 (Accessed: 22 November 2021).

Matsouka, K. and Mihail, D.M. (2016) ‘Graduates’ employability: what do graduates and employers think?’ Industry and Higher Education, 30(5), pp. 321–326. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422216663719 (Accessed: 26 March 2022).

Small, L., Shacklock, K. and Marchant, T. (2018) ‘Employability: a contemporary review for higher education stakeholders’, Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 70(1), pp. 148‒166. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2017.1394355 (Accessed: 22 November 2021).

Succi, C. and Canovi, M. (2020) ‘Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students’ and employers’ perceptions’, Studies in Higher Education, 45(9), pp. 1834‒1847. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420 (Accessed: 22 November 2021).

University of Greenwich (2022) This is our time: University of Greenwich Strategy 2030. Available at: https://www.gre.ac.uk/articles/public-relations/this-is-our-time (26 March 2022).

Zabeli, N., Kaçaniku, F. and Koliqi, D. (2021) ‘Towards the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education: challenges and prospects in Kosovo’, Cogent Education, 8(1),1859438. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1859438 (Accessed: 26 November 2021).

Dr Duyen Chu is a Senior Lecturer in Strategy and Management at Greenwich Business School, University of Greenwich. Entering the higher education sector after many years working in industry, he is a passionate educator. Dr Duyen Chu has been teaching in different national and international higher education institutions, including Swinburne University of Technology, University of Lincoln and University of Greenwich. He has been proactively engaging with different professional bodies, including Advance HE and Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS). He holds fellowship of Advance HE and is a Certified Management and Business Educator (CMBE) of CABS, a member of Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) Forum, and a reviewer of the annual CPD review of CMBE/CABS. Dr Duyen Chu has been doing both disciplinary and pedagogical research, especially innovative pedagogy, inclusivity in higher education and student employability optimisation. He is also a reviewer and session chair of different journals and conferences, including Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, EURAM conference, SHIFT, GBS Learning and Teaching Festival.

Dr Qijun Zhou is a lecturer in the School of Business, Operations and Strategy in the Greenwich Business School. He received his Ph.D in Management from University of Glasgow and worked as a post-doc research assistant before joining University of Greenwich. Qijun is the Module leader for MARK1190 Foundations of Scholarship and BUSI1626 Strategy Management. Qijun’s research work focused on new product development, supply chain finance, ambidextrous organisations, and dynamic capability. He is also interested in increasing student employability focusing on transferable skills and has conducted research on using simulation game for teaching in operations management.

Dr Alistair Bogaars is a Lecturer in the School of Business, Operations and Strategy in the Greenwich Business School. Prior to this Alistair was employed as a Teaching Fellow in the Department for Systems Management and Strategy from September 2020-2021. Alistair is the Programme Leader for the BA Hons Business with Marketing and Business with Finance Programmes. Alistair is the Module Leader for the TRAN 1063 Introduction to Logistics and Transport (Level 4), BUSI 1318 Advanced Project Management (Level 6) and TRAN 1028 Sustainable Transport (Level 6) modules.

Alistair completed his PhD with the Greenwich Business School in March 2021 – his thesis examined fuel and transport poverty, with respect to Government policy in the UK. Alistair completed an MSc Environmental Conservation (2010) and BSc Environmental Biology with European Study (1997) with the School of Science at the University of Greenwich.

Alistair has a keen interest in pedagogy research and is participating in several projects supported by the Scholarship Excellence in Business Education (SEBE) group at the University of Greenwich. Alistair has been an active member of the Connected Cities Research Group (CCRG) since 2017. Alistair has been a member of the University of Greenwich LGBT+ Staff Community since December 2020.