Alistair Bogaars, Yan Li and Shuai Zhang

The challenge

We were challenged to think about incorporating authentic assessment principles into the core first year project management module by our Head of Department. We would like to share our approach to this challenge in our blog.

What is authentic assessment?

An authentic assessment requires the completion of ‘real-world tasks’ that are designed to demonstrate how students can apply the knowledge and skills they have learned (Mueller, 2018). Authentic assessments require students to actively use the theory they have been taught in a context that is ‘actual, contemporary and practical’ (Brown, 2015).

A wide range of assessment types can be classed as authentic, including presentations, projects, posters, portfolios, case studies and group coursework (Fox et al., 2017). The most authentic form of assessment is where ‘students set their own assessment,’ perhaps unsurprisingly exams are thought to be the least authentic (Dinning, 2018).

Herrington and Herrington (2008) have set out the nine characteristics of authentic learning:

- authentic context – presenting students with realistic problems that retain the complexity of the real world

- authentic activities – requiring students to complete activities that are not well designed, thus reflecting the complexities of the real world

- expert performances – exposing students to expert practitioner behaviour to enable them to model real-world practice

- multiple roles and perspectives – providing students with a multitude of perspectives so that they can examine problems from a variety of points of view

- collaborative construction of knowledge – promoting collaboration between students in group work by using appropriate tasks and communication technology

- reflection – providing students with an opportunity to reflect on their learning through authentic and meaningful activities

- articulation – requiring students to present their work using an appropriate forum, such as classes, conferences and seminars

- coaching and scaffolding – relating to the role of the tutor and other students by supporting learning, for example by coaching at critical points along with the scaffolding of support to assist students experiencing difficulties with the task

- authentic assessment – integrating the assessment into the activity, such as the provision of assessment that has been integrated into the learning associated with tasks.

These characteristics are important as they provide a useful guide for the design of authentic learning that educators can draw on when preparing their curriculum. We recommend drawing on the characteristics that most apply to your module topic and assessment type. We have focused on the integration of the authentic assessment characteristics into a Level 4 Project Management module.

What are the advantages of authentic assessment?

Authentic assessment has the potential to motivate and inspire students to explore attributes of their own learning and the real world that could have been overlooked (Lombardi, 2008). The Advance HE deems authentic assessment methods to be ‘intrinsically worthwhile’ as they can develop the ‘future employability’ of students (Ball et al., 2012). We are aware that tutors are increasingly being asked to consider employability when designing teaching activities on modules and programmes. The use of authentic assessment creates outputs that can provide students and higher education institutions (HEIs) with evidence for future employers and policy makers (Fox et al., 2017).

Pitchford, Owen and Stevens (2020) present their vision of higher education as an experiential journey for students which facilitates effective learning about the discipline and the real world. This means that the link between assessment and the real world is a crucial factor in this approach as it permits students to demonstrate their potential contribution.

Wider advantages include diversification of the validity, authenticity and inclusivity of assessments (Ball et al., 2012). These values link into strategic objectives at HEIs, such as the University of Greenwich (2021), as they impact on the student experience.

What are the challenges of authentic assessment?

Student concerns about the nature of authentic assessments include uncertainty about what they need to do and how it will be marked (DeCastro-Ambrosetti and Cho, 2005). There may also be concerns about language problems and group work, particularly amongst international students (Bohemia and Davison, 2012). Keeling, Woodlee and Maher (2013) shared their experiences of running an authentic assessment exercise with students on the Master’s degree in Student Affairs at the University of South Carolina, pointing out that whilst using an ‘iterative assessment cycle’ helped, many students found that the process of authentic assessment was ‘chaotic, messy, frustrating and unpredictable.’ However, this in many ways reflects the real world, which is inherently messy at times. This aspect could help prepare students for situations that they are likely to face either on work placements or in their future employment.

Academic staff have reported the requirements of institutional regulatory conformance, constraints on time and size of student cohorts as the main challenges associated with the development of authentic assessment for students (Dinning, 2018). The link between academics, time (workload) and authentic assessment has a long history. Burtner (2000) raised an important issue around the implementation of authentic assessments, such as written portfolios in engineering faculties, where there was resistance to the ‘extraordinary time commitment’ required to evaluate these portfolios.

Student engagement is a critical challenge facing all universities. Authentic assessment can be used to ‘foster student engagement,’ but this means that faculties need to recognise that additional resources will be needed for implementation (Hart et al., 2011). Improved student engagement is a key reason why we considered implementing authentic assessment, as it was a challenge experienced by tutors on the Level 4 Project Management module.

What are the solutions to the challenges of authentic assessment?

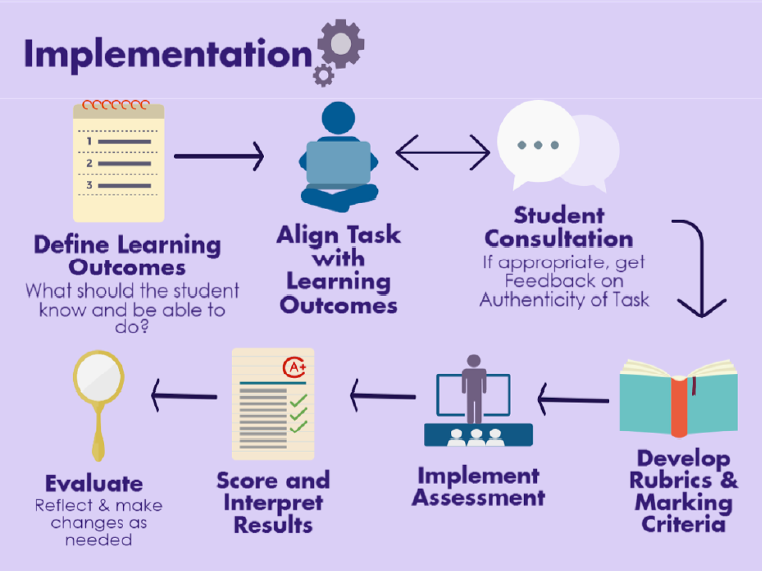

Fox et al. (2017) have proposed an approach to support educators with the implementation of authentic assessment, which is shown in Figure 1. This approach incorporates an element of curriculum design that involves active collaboration with students (if appropriate), which is a way to test the authenticity of the task prior to implementation.

Figure 1 ‘Keeping it Real’: A brief guide to implementing authentic assessments (Fox et al., 2017)

Student consultation may well be challenging for tutors who teach a new group of students each year, but it is worthy of consideration. Herrington and Herrington (2008) point out that students are rarely given an opportunity to collaborate in their learning, even though it is increasingly possible both in the classroom and using online platforms. It is important for educators to consider how much education is being done to students, rather than being done by them, particularly at Level 4.

Evaluation is a valuable component of authentic assessment, which should ideally be carried out by educators and students throughout module delivery (DeCastro-Ambrosetti and Cho, 2005). The feedback and experiences of students can be used by educators to develop future authentic assessments (Fox et al., 2017). This is something that many tutors will be familiar with through the Evasys surveys commonly used by universities.

Is authentic assessment design a solution for tackling assessment misconduct?

Birks et al. (2020) found that investment in assessment design was thought by academics to be crucial in the prevention of assessment misconduct, with ‘authentic and personalised’ assessments playing a critical role. There is, however, an interesting counterargument to this narrative. Ellis et al. (2020) state that there is an assumption that students cheat due to a lack of motivation to do ‘inauthentic’ assignments. The underlying context is ‘contract cheating,’ where a student submits an assessment that has been completed by a third party (Harper et al., 2019).

Research has shown that the reasons for cheating by students are multiple and complex (Ellis et al., 2020). There is a lack of empirical evidence on why authentic assessment could address the reasons for students engaging in ‘contract cheating,’ but the belief is linked to the idea that it could reduce the desire, or make it too complex to cheat (Ellis et al., 2020).

These are all important ideas for academics to consider when designing assessments. Arguably any changes that discourage or make it less desirable for students to cheat are beneficial. However, whilst best practice approaches to assessment design were considered a crucial factor in the prevention of academic misconduct, it should be acknowledged that students will cheat regardless of the assessment format (Birks et al., 2020).

Next steps in authentic assessment

We propose to trial the approaches to authentic assessment obtained from the literature (Brown, 2015; Fox et al., 2017; Dinning, 2018) with a Level 4 Project Management module at the Greenwich Business School. This module has been impacted by the challenges of student engagement, academic misconduct and lower Evasys scores.

We are mindful of the challenges posed by assessment misconduct, but we intend to make our learning and assessment more authentic. We will take steps to use up-to-date case studies in class and avoid using ‘famous’ or well-known case studies in our assessments. We will encourage students to develop their own ‘organic’ business ideas and to reflect on their in-class activities. These are factors that we feel will add a higher level of authenticity to assessments and lead to improvements in the Evasys score over the next year.

References

Ball, S., Bew, C., Bloxham, S., Brown, S., Kleinman, P., May, H., McDowell, L., Morris, E., Orr, S., Payne, E., Price, M., Rust, C., Smith, B. and Waterfield, J. (2012) A marked improvement: transforming assessment in higher education, York: The Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/marked-improvement (Accessed: 2 May 2022).

Bohemia, E. and Davison, G. (2012) ‘Authentic learning: the gift project’, Design and Technology Education: an International Journal, 17(2). Available at: https://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1731 (Accessed: 4 May 2022).

Brown, S. (2015) ‘Authentic assessment: using assessment to help students learn’, RELIEVE, 20(2), pp. 1–8.

Burtner, J. (2000) ‘The changing role of assessment in engineering education: a review of the literature’, in ASEE Southeast Section Conference. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.491.8350 (Accessed: 2 July 2022).

DeCastro-Ambrosetti, D. and Cho, G. (2005) ‘Synergism in learning: a critical reflection of authentic assessment’, High School Journal, University of North Carolina Press, 89(1), pp. 57–62.

Dinning, T. (2018) ‘Assessment of entrepreneurship in higher education: an evaluation of current practices and proposals for increasing authenticity’, Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching, 11(2). Available at: https://journals.gre.ac.uk/index.php/compass/article/view/774 (Accessed: 2 May 2022).

Ellis, C., van Haeringen, K., Harper, R., Bretag, T., Zucker, I., McBride, S., Rozenberg, P., Newton, P. and Saddiqui, S. (2020) ‘Does authentic assessment assure academic integrity? Evidence from contract cheating data’, Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), pp. 454–469.

Fox, J., Freeman, S., Hughes, N. and Murphy, V. (2017) ‘Keeping it real’: a review of the benefits, challenges and steps towards implementing authentic assessment, All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 9(3).

Harper, R., Bretag, T., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., Saddiqui, S. and van Haeringen, K. (2019) ‘Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university staff’, Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), pp. 1857–1873.

Hart, C., Hammer, S., Collins, P. and Chardon, T. (2011) ‘The real deal: using authentic assessment to promote student engagement in the first and second years of a regional law program’, Legal Education Review, Sydney, Australia, Australasian Law Teachers’ Association, 21(1), pp. 97–121.

Herrington, J. (2006) Authentic e-learning in higher education: design principles for authentic learning environments and tasks, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia.

Herrington, A. and Herrington, J. (2008) What is an authentic learning environment? Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia.

Keeling, S. M., Woodlee, K. M. and Maher, M. A. (2013) ‘Assessment is not a spectator sport: experiencing authentic assessment in the classroom’, Assessment Update, 25(5), pp. 1–16.

Lombardi, M. (2008) ‘Making the grade: the role of assessment in authentic learning’, EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, 1, pp. 1–16.

Mueller, J. (2018) What is Authentic Assessment? Authentic Assessment Toolbox. Available at: http://jfmueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/toolbox/whatisit.htm (Accessed: 3 May 2022).

Pitchford, A., Owen, D. and Stevens, E. (2020) A handbook for authentic learning in higher education: transformational learning through real world experiences. London: Routledge.

University of Greenwich (2021) This is our time: University of Greenwich strategy 2021‒ 2030, University of Greenwich. Available at: https://docs.gre.ac.uk/rep/communications-and-recruitment/this-is-our-time-university-of-greenwich-strategy-2030 (Accessed: 27 July 2021).

Dr Alistair Bogaars is a Lecturer in the School of Business, Operations and Strategy in the Greenwich Business School, prior to this Alistair was employed as a Teaching Fellow in the Department for Systems Management and Strategy from September 2020-2021. Alistair is the Programme Leader for the BA Hons Business with Marketing and Business with Finance Programmes. Alistair is the Module Leader for the TRAN 1063 Introduction to Logistics and Transport (Level 4), BUSI 1318 Advanced Project Management (Level 6) and TRAN 1028 Sustainable Transport (Level 6) modules.

Alistair completed his PhD with the Greenwich Business School in March 2021 – his thesis examined fuel and transport poverty, with respect to Government policy in the UK. Alistair completed an MSc Environmental Conservation (2010) and BSc Environmental Biology with European Study (1997) with the School of Science at the University of Greenwich.

Alistair has a keen interest in pedagogy research and is participating in several projects supported by the Scholarship Excellence in Business Education (SEBE) group at the University of Greenwich. Alistair has been an active member of the Connected Cities Research Group (CCRG) since 2017. Alistair has been a member of the University of Greenwich LGBT+ Staff Community since December 2020.

Dr. Yan Li completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on business model innovation, eco-efficiency and capability. She got her MPhil degree from the University Cambridge and BSC degree at Fudan University.

Dr. Shuai Zhang joined the University of Greenwich in 2018, after he completed his Ph.D at the University of Cambridge. He got Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Birmingham and University College London (UCL). He employs a qualitative approach to study the ecosystem for multinational companies in manufacturing industry.