Ronald Gibson and Raluca Marinciu

The current neo-liberal valuation of higher education views universities as the provider of labour market resources and improved student job prospects for those undertaking a business subject (Green, Hammer and Star, 2009; Holmes, 2013; Tomlinson, 2012; Tymon, 2013). Employability literature debates the postmodern internship as the answer to prepare students for work (Gault et al., 2000), gain transferable skills (Hillman and Rotham, 2007) and improve long-term employability (Hergert, 2009). However, not all internships are created equal, or lead to graduate level employment. In this piece we are referring to an internship as being a minimum of nine months of work experience, which can also be identified as a ‘placement year’.

There is a gap in understanding how internships translate into graduate outcome high-skilled roles (GOHS), what impact a university has on achieving them, and how to forecast whether an internship will lead to a graduate role. This blog post follows from a presentation at the 2022 University of Greenwich Learning and Teaching Festival and proposes a study to develop an internship value metric through an employer survey to support the understanding of how an internship can contribute towards a student successfully securing a GOHS in the market as measured by the Office for Students (OfS) Graduate Outcomes (GO) survey.

Universities have been critiqued for their inability to teach students the soft skills required to be successful in the workplace (Gault et al., 2000) and instead have been blamed for a skills gap shortage in the labour market (Hillman and Rotham, 2007). To address this deficiency, business schools have begun to incorporate internships so that students can learn specific job-related skills.

There is very little research available in understanding the ultimate correlation between internships and students gaining the required skills to enter the graduate job market and be successful in the workplace. Our proposal to develop an internship value metric is a solution to shed light on the skills learned within an internship. This will contribute to creating a framework that universities can use to evaluate skills development and the effect on the graduate career.

How a graduate outcome is calculated

Graduate outcomes are calculated by the annual GO survey held 1.5 years post-graduation. While there is a list of questions asked of students, the main question, and the one that is publicly reported for universities, is the percentage of students who are deemed to be in a high-skilled graduate role. The first question asked is ‘job title’ followed by probing questions of skills used in the role. If the job title matches the SOC (Standard Occupational Classification) code for a high-skilled role, and the skills used match those expected in that role according to the ESCO (European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations) skills description, the graduate is considered to be in a GOHS role. This outcome is determined by the student’s ability to clearly state the role and the skills used.

The importance of graduate outcome position

The OfS places pressure on universities to examine and improve the outcomes of graduates, deeming those with low graduate outcomes as poor-value. Pressures are then placed on university senior management to fix the measured outcome through employability supports, reduce student numbers on the poor-value programme (Morgan, 2022), or remove the programme altogether, which is currently strangling many arts programmes (Weale, 2022).

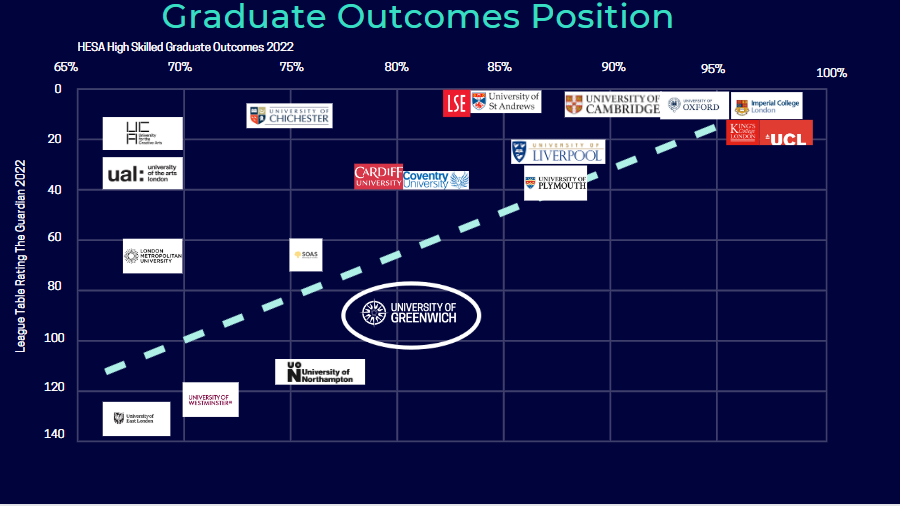

As graduate outcomes are an important measurement in the UK TEF (Teaching Excellence Framework) and LTR (League Table Ranking), the ability of students to attain graduate roles directly affects a university’s brand value. The higher the percentage of graduate outcomes, the higher ranked the school on the LTR. In our analysis there are some outliers, for example institutions focusing on the arts versus those who have higher enrolments in professional programmes such as health and social care. Those with programmes with direct routes to skilled employment are bound to have a higher graduate outcome result while those who have a variance of job title have lower GOHS outcomes. The universities for this study were chosen as a sample representative of the type of higher education institutions currently operating in the UK market, including Russell Group and top universities, universities similar to University of Greenwich in terms of programmes offered, and specialist universities where a trend in graduate outcomes can be identified.

Students use LTR to choose the ‘better’ school to attend (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2015) and employers use LTR to determine the skill level of a new hire (Christie, 2017). League table ranking then is marketing the value of the credential and is driven by the OfS graduate outcome survey results.

Developing a metric that supports skill measurement

To develop a measurement tool, we first need to understand the areas of skills values sought in the graduate labour market, categorising these into graduate variable clusters. We propose to begin with the seven values theorised by Cattani and Pedrini (2021): knowledge (commercial acumen), skills, attitudes, values, working style, job description (activities) and working conditions.

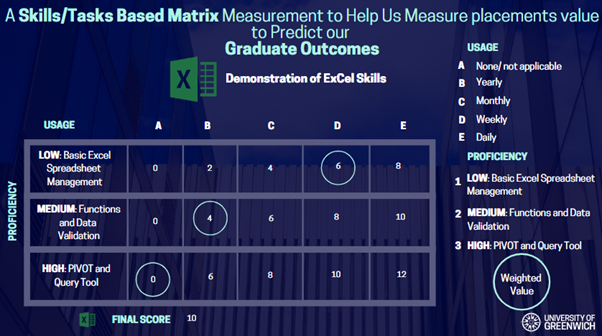

Within the business faculty we aim to create a learning contract agreement for internships. The aim is to improve graduate prospects, monitor those areas and improve understanding of our internship provision. Within the learning contract we plan to develop a skills/task proficiency survey measuring the level of usage and level of each skill proficiency while on placement. Underlying this combination will be a weighted value intended to attribute value to graduate outcome skills. Higher total values would be assumed to increase the likelihood of skills usage and attractiveness in high-skilled positions.

There is a concern on deciding skill weights and on rubric proficiency level cut-offs. While for software proficiency it may be easy to determine differences of skill level, more subjective skills such as communication or personal values will be difficult to determine.

In the figure above, the example shown would read as weekly low proficiency, yearly medium proficiency and no high proficiency, equating to a weighted score of 10/30.

Research design

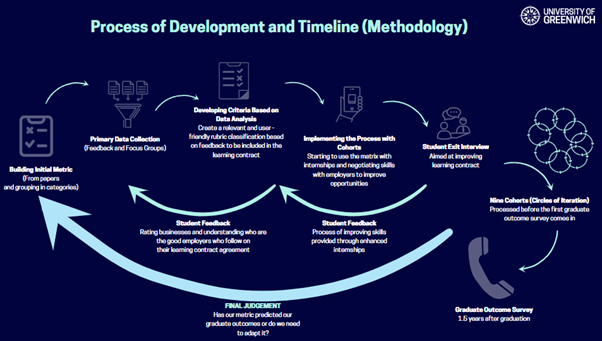

The process of development has used an exploratory approach. Previous research on placements has concentrated on binary outcomes, and the data focuses on whether a student participates in a placement or not but does not take the quality of the placement into account. Due to the lack of a study analysing the relationship between the quality of student placements and their graduate outcomes, we aim to employ an exploratory method to identify the significant factors (Cohen et al., 2017).

Our plan of action in developing the metric and survey is to:

- Step (1) gather information from SOC code classifications, ESCO descriptions and papers on graduate outcomes and the graduate skills gap

- Step (2) create focus groups with employer partners to aid in the development of proficiency rubrics and usage levels and provide some initial thoughts on weighted levels

- Step (3) create a user-friendly online survey for employers and run a pilot

- Step (4) use the survey with each cohort of placement students and feed back to the learning contracts, adjusting the survey as needed

- Step (5) carry out student exit interviews aimed at improving the learning contract and understanding what students are/are not learning on placements in order to improve skills and supplement missing skills to better match the needs of graduate roles (nine iterations will pass before the first GO survey results)

- Step (6) use the first GO survey results to compare with initial iteration. Test to compare metric with GOHS outcomes. Use to rework skills weighting in the survey.

It is only after the OfS Graduate Outcomes survey results are returned that we will know the effect of our efforts and the usefulness of our skills survey measurement. Prior to the GO survey results we can only make assumptions that the metric is measuring skills learned, with a check at the student exit for each cohort. These will only be assumed improvements of GO outcomes, and we would not know if there really is a possibility of using the metric as a forecasting tool until we begin to receive the final GOHS results.

We believe this process will improve our practice, provide more detailed knowledge of what the students are doing and learning in placement ‒ or not. Furthermore, it will provide a tighter connection with employers, especially when using the tool during internship check-ins.

Conclusion

Students enter postgraduate study for a number of reasons, one of which has been selected by the Office for Students as a measurement of the value of higher education, namely to find graduate employment within 1.5 years of completion of their degree. The Graduate Outcomes survey is a metric embedded into the Teaching Excellence Framework and League Table Rankings, making it one of the most important measures used to judge the value of higher education (Kethuda, 2022). Yet, the ability to secure a graduate position in the labour market is determined by more than a credential, and it has been assumed that universities on their own are unable to provide the skills sought by the labour market. The impact graduates and their performance in the labour market have on a university’s reputation and future cohorts of students has also been recognised (Drydakis, 2014). This has led to an increase in programmes embedding internship placements in order to increase the likelihood of learning on-the-job skills, making students work-ready and able to secure a graduate level position.

As not all internships are created equal, and many do not lead to graduate roles, there is a need for universities to aid in the process. It is through a learning contract between the university, the employer and the student, with a focus on skills proficiency building, that we intend to improve the likelihood of achieving high-skilled graduate outcomes and create a metric which may aid in forecasting this achievement. In the long run, we hope to improve graduate outcomes for our students and for our programmes and, if successful, be able to roll the project out to other faculties and schools.

References

Cattani, L. and Pedrini, G. (2021) ‘Opening the black-box of graduates’ horizontal skills: diverging labour market outcomes in Italy’, Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), pp. 2387‒2404.

Cheng, M., Adekola, O., Albia, J. and Cai, S. (2021) ‘Employability in higher education: a review of key stakeholders’ perspectives’, Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 16(1), pp. 16‒31.

Christie, F. (2017) ‘The reporting of university league table employability rankings: a critical review’, Journal of Education and Work, 30(4), pp. 403‒418.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. (2017) Research methods in education. 8th edn. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis.

Drydakis, N. (2014) ‘Economics applicants in the UK labour market: university reputation and employment outcomes’, International Journal of Manpower, 36(3), pp. 296‒333.

Gault, J., Leach, E. and Duey, M. (2010) ‘Effects of business internships on job marketability: the employers’ perspective’, Education and Training, 52(1), pp. 76–88.

Green, W., Hammer, S. and Star, C. (2009) ‘Facing up to the challenge: why is it so hard to develop graduate attributes?’ Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), pp. 17‒29.

Hemsley-Brown, J. and Oplatka, I. (2015) ‘University choice: what do we know, what don’t we know and what do we still need to find out?’ International Journal of Educational Management, 29(3), pp. 254‒274.

Hergert, M. (2009) ‘Student perceptions of the value of internships in business education’, American Journal of Business Education, 2(8), pp. 9‒14.

HESA (2022) Graduate Outcomes, Available at:https://www.hesa.ac.uk/innovation/outcomes (Accessed: 4 September 2022)

Hillman, K. and Rotham, S. (2007) ‘Movements of non-metropolitan youth towards the cities’, Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth, Research Report 50. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Holmes, L. (2013) ‘Competing perspectives on graduate employability: possession, position or process?’ Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), pp. 538‒554.

Kethuda, O. (2022) ‘Evaluating the influence of university ranking on the credibility and perceived differentiation of university brands’, Journal of marketing for Higher Education, 1(2), pp. 1‒18

Morgan, J. (2022) ‘English student number caps “set to use new outcomes measures”’, Times Higher Education, 6 July. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/english-student-number-caps-set-use-new-outcomes-measures (Accessed: 4 September 2022).

Rhoden-Paul, A. (2015) ‘Get a job or get out: the tough reality for international students’, The Guardian, 2 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/jul/02/get-a-job-or-get-out-the-tough-reality-for-international-students (Accessed: 4 September 2022).

The Guardian (2022) The best UK universities 2022 – rankings, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/ng-interactive/2021/sep/11/the-best-uk-universities-2022-rankings (Accessed: 4 September 2022)

Tomlinson, M. (2012) ‘Graduate employability: a review of conceptual and empirical themes’, Higher Education Policy, 25, pp. 407–431.

Tymon, A. (2013) ‘The student perspective on employability’, Studies in Higher Education, 38(6), pp. 841‒856.

Weale, S. (2022) ‘Philip Pullman leads outcry after Sheffield Hallam withdraws English lit degree’, The Guardian, 27 June, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/jun/27/sheffield-hallam-university-suspends-low-value-english-literature-degree (Accessed: 4 September 2022).

Ron is the MA International Business Programme Leader, Module Leader for the MBA internship placement year, and a MERIT research fellow at the University of Greenwich.

Raluca is originally from Transylvania, Romania from a city called Sibiu. Raluca came to London as an international student and is an alumni of the University of Greenwich. She has secured her graduate role with the University and has worked for the past five years focusing on international partnerships supporting transnational education performance at University of Greenwich and in employability office supporting networking events and building relationships with employers. Raluca has also started her teaching fellowship and is a personal and placement tutor across different programmes in the University. In addition, Raluca is a passionate volunteer and is researching in subjects such as social justice and equal opportunities, pursuing a PhD in that area.