Challenges of Conducting Virtual Classes

I find that when I am teaching online, I am really struggling when I cannot see nor hear the audience. It feels a bit like talking into a black hole as there is no affirmation. I feel that many colleagues may also find themselves in the same situation as well.

The Covid-19 social distancing measures within teaching, learning and assessment activities have brought about unprecedented changes. These changes set out a very different educational context from our conventional practices.

The new way of teaching and learning has pushed educators around the world to learn new skills. In a short time, we have had to embrace a new way of teaching and engaging with students remotely. It was a huge challenge to multitask (running seminar activities and checking the chat at the same time with multiple devices) for a novice like me to run an interactive virtual seminar. Without a doubt, the preparation time for a virtual class is much more than a conventional seminar class. This is because I have to think of ways to keep my students engaged behind their screens.

Challenges of Virtual Learning for Students

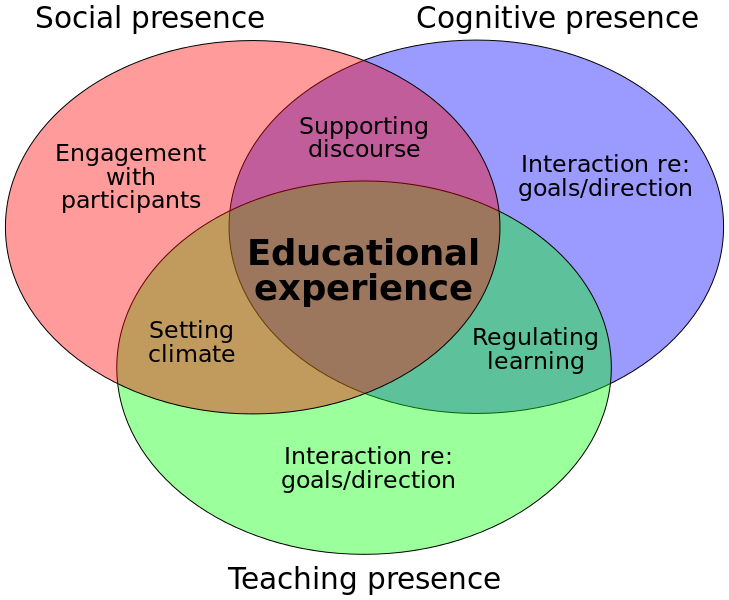

Source: Garrison, Anderson and Archer, 2001

There are many challenges associated with virtual learning for students, despite great efforts to deliver good educational experience to all students. The challenge of social presence is still a pressing issue, this is especially the case for certain groups of students such as the disadvantaged individuals without proper devices. Also, those whose support for online learning is limited and students from high uncertainty avoidance societies may experience more difficulties with moving to online learning. According to Hofstede (2001), uncertainty avoidance reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with anxiety by minimising uncertainty. Thus, students from high uncertainty avoidance societies are more resistant to new changes.

According to Garrison (2019, p. 352), social presence is “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities”. Students who are shy on camera was harder than through non refuse to turn on their camera for classes and discussions was harder for me to build an emotional connection with students through non-verbal cues such as eye contact. On the other hand, it also poses a great challenge for students to build trust among peers in a virtual environment.

Initially, I was puzzled and felt discouraged with students’ engagement in virtual classes, but later I learned that cyberspace itself has a culture and it is not simply a neutral and value-free platform for exchange (Chase et al., 2002). Basically, cyberspace culture is formed and predominated by the majority of the active users. Hence, disadvantaged and marginal groups might be excluded. Therefore, students with little confidence are afraid to share their views because they are afraid of the risk of miscommunication and judgment by their peers. In addition, I also learned that electronic communication is not internationally standardised in the intercultural communications context, therefore, I have to be culturally conscious to avoid chances of miscommunication.

Moreover, without having non-verbal cues to intuit meanings (and not being able to give or save face) further refrains students in participating group works or virtual discussions. Notably, students from low uncertainty avoidance cultures are more willing to participate in virtual discussions and there is a propensity that they will dominate the group activities. On the contrary, students from high uncertainty avoidance cultures are often quiet and shy away from group activities.

What have I done to help?

To break the fear of insecurity and ease their self-condemnation when making mistakes in learning, I tend to use anonymous activities in the first two weeks of my virtual class to encourage participation (Chen, 2019). For example, I use Teams whiteboard activity, polls, kahoot or mentimenter. Nevertheless, not all students are in favour of these online activities. I found out that some students are not familiar with these online activities and some students do not have multiple devices to switch around for game-based learning activity such as kahoot. As a result, I have to accommodate students’ constraints and use the right tools to ensure that my virtual activities are accessible to all students. For example, I use the breakout rooms function that do not require multiple devices to participate.

In addition, I realised that a longer waiting time help improves participation rate and deepen academic discourse (Black et al., 2014). However, I often feel awkward with the silent moments. I always expect instant replies from my students and neglected that some students might need a more time to prepare and present their ideas.

Since most students refused to turn on their camera for virtual class, voice projection became a powerful medium to build emotional connection with students. Voice projection is important as in a virtual environment eye contact and non-verbal cues are limited. I believe that the use of positive and high energy tone of voice in teaching is effective to build emotional connection with students. For instance, I will make full use of tone and pace like an entertainer to capture and hold students’ attention. I often clap for my students over the screen and occasionally I will leap from my chair when I hear good answers from them. I am convinced that our voice and body language will have a huge impact on students’ virtual learning experience.

What have I learned?

After more than a year of conducting virtual classes, I can conclude that the changes brought by the covid-19 pandemic have provided us a good opportunity to reflect and rethink about our role and practices as a facilitator. In this year, I learned to reposition myself from a teacher role to a facilitator role. In the face-to-face setting, I had propensity to use the traditional teacher-centered approach in my delivery. However, I realised that this way of teaching was ineffective to engage with my students, especially in a virtual environment. Therefore, I learned to shift from teacher-centered to student-centered approach. I realised that the dialectic approach is a good way to create interest and engage deeper with students. I also learned to use flipped approach and inquiry-based learning activities to better facilitate learning. For example, I use debates, role play and group discussions in my seminars to help improve engagement and to enhance teamwork and collaboration among students.

Lastly, I find that some students can excel well regardless in face-to-face or virtual learning setting. I did find that less able or vulnerable students are the group of individuals that needed extra support to continue learning in these highly uncertain times. My main role as an online instructor is to enable and support every student to learn well and progress according to their needs and their ambitions.

Blog Author

Andrew Woon

Teaching Fellow in Business Studies

Department of Systems Management and Strategy

Greenwich Business School

a.s.woon@greenwich.ac.uk

References

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B. and Wiliam, D., 2004. Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi delta kappan, 86(1), pp.8-21.

Chase, M., Macfadyen, L., Reeder, K. & Roche, J., 2002. Intercultural Challenges in Networked Learning: Hard Technologies Meet Soft Skills Hard Technologies Meet Soft Skills. Berlin, s.n.

Chen, C., 2019. Using Anonymity in Online Interactive EFL Learning. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 15(1), pp. 204-218.

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Communities of inquiry in online learning: Social, teaching and cognitive presence. In C. Howard et al. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance and online learning (2nd ed., pp. 352-355). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Garrison, D.R., Anderson, T., Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education. 13(1), 5-9.

Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.