In 1855, Robert Bonner of the New York Ledger (NYL) started serialising “Fanny Fern” (Sara Payton Willis). He advertised that she was paid $100 per column so that readers could gauge the exact amount she got paid – and could value her writing accordingly. It was at this point that sales – and the profits – of the NYL rose to unprecedented heights. This sent a clear signal across the Atlantic that America, with whom a copyright agreement still did not exist, could now provide rich and proven fodder for the cheap periodical market. The result was that The Family Herald pirated Fanny Fern’s two serial novels from NYL in 1855-6 and other papers widely plagiarised and imitated her columns.

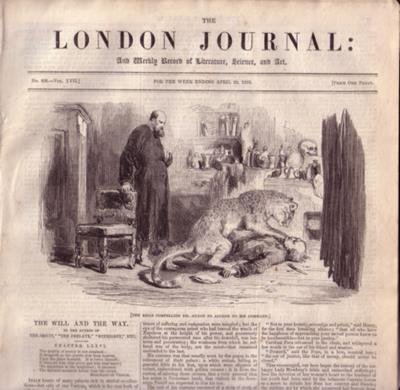

The London Journal, The Family Herald’s main rival, didn’t want to publish the same thing at the same time and so researched the American mass market. It discovered a tale called The Lost Heiress that the Saturday Evening Post had just published. The London Journal started running it a month after Fanny Fern’s novel had begun in The Family Herald, having changed the title from The Lost Heiress to The True and False Heiress. It published the serial anonymously until its very last episode, when it revealed the author to be E.D.E.N. Southworth. The serial was apparently very successful.

Back in America, this was noticed by Robert Bonner who invited Southworth to write exclusively for the New York Ledger. She started her series of “exclusive” novels for him in 1857 and became one of the most widely read and reprinted authors of the entire nineteenth century. This in turn caused the Ledger’s sales to rise ever higher and The London Journal and other penny periodicals to print more of her stories.

As for why I’ve put 1883 as the terminus of my study you may think that’s curious when copyright plays such an important part in my narrative and the US started regulating international copyright in 1891. But two of the authors I’m focussing on were dead by then – and there are reasons why Southworth appeared in the British mass market periodical much less after 1868. When in 1883 The London Journal made the serious mistake of trying to serialise Zola and lost a large number of readers, they chose to rescue the situation by serialising a Harriet Lewis novel even though she had died 5 years previously. What the original of that novel is I haven’t been able to establish. But I can say that as far as I been able to discover, it hadn’t been published in Britain before and that her name was considered a remedy for the ills of declining circulation. It’s possible of course that she never wrote the London Journal serial: they might have only added her famous name to it. Be that as it may, what appear in Britain are only reprints of works by these three women. 1883 therefore marks a watershed insofar as works new to the market are concerned.

The above is all background to the question I really want to address in these three blog posts which is whether the literary property of these American women was “pirated” – stolen morally (if even if such action was legal) – by the British periodicals.

To answer the question is actually rather difficult, for it depends partly on the definition of the term “piracy” and partly on information that is lacking. There is little doubt that Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Fanny Fern’s writings were pirated in Britain in the same way that the French novels of Sue and Dumas had been in the 1840s. But the cases of the writers I’m talking of present complications.

While I only want to talk of the three novelists in The London Journal I’ve mentioned, May Agnes Fleming, EDEN Southworth and Harriet Lewis, they will provide varied examples of how American women writers were not simply melodramatic victims of wicked men in Europe. Rather I’ve found that, unlike Isabel Archer in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady they could actually benefit from and actively manipulate the system of transatlantic cultural exchange.

First then, May Agnes Fleming. Her first two novels in The London Journal were pirated in a quite straightforward sense, yet this surprisingly worked to her advantage. In 1868, Fleming had signed an exclusive contract with the Philadelphia fiction weekly Saturday Night. The following year The London Journal took from it a novel originally called The Heiress of Glengower, renaming it The Sister’s Crime and publishing it anonymously. Several papers in America pirated it in return, unaware that it was already copyright in America. It was so popular that when it was legally stopped in the American papers, a “bidding war” for the author resulted. The outcome was victory for Fleming: she accepted the offer of the New York Weekly which immediately tripled her income, later signed a contract that gave her 15% royalties on the sales of her novels in volume format, and, from 1872, made an arrangement to send The London Journal advance sheets for £12 per instalment. Altogether, this gave her $10,000 a year. She didn’t do too badly out that initial piracy.

E.D.E.N. Southworth’s relation with The London Journal was even more complicated. Her first three novels in the magazine were pretty certainly pirated and, like Mrs Stowe before her, she came to England to stop this – for residence in Britain gave copyright protection. However, in the year Southworth came, 1859, although she was under exclusive contract to Robert Bonner, she must have arranged to give advance sheets of her most famous novel, The Hidden Hand, to the former owner of The London Journal, George Stiff, as it appeared in another magazine of his, The Guide, only a week after it came out in the New York Ledger. When Stiff rebought The London Journal he continued his relationship with her. The next year, 1860, The London Journal would publish two more novels by Southworth again only a week after their New York appearance. Hypocritically, in an open letter to readers of the Ledger (10 March 1860) Southworth had just complained about being plagiarised in Britain . In 1861, a novel of hers even appeared in London before it came out in New York (Eudora).

Sailing ever closer to the wind, she wrote Captain Rock’s Pet especially for The London Journal. After this, none of her novels appear in it for two years. Stiff had again sold The London Journal and instead, some of her novels appear in his new magazine, the London Reader anonymously. The next Southworth novel in The London Journal, Sylvia (1864), was probably pirated, as it is a version of Hickory Hall, a serial that had appeared in the National Era in 1850. But such is impossible in the case of her next three novels in The London Journal, Left Alone, The Manhater and The Malediction. These again all appear either a week before or a week after they are printed in the Ledger. Southworth’s last novel in The London Journal, The Double Life (1869), is a version of another National Era serial from twenty years previously, which may again suggest piracy. Perhaps Bonner prevented her from sending more advance sheets. Southworth wrote a particularly strong declaration of loyalty to him dated 12 January 1869, which may be read as finally accepting that she really was under exclusive contract to him. Perhaps it is because of this that The London Journal turned to another and younger New York Ledger staple, also under supposedly exclusive contract to Robert Bonner, Harriet Lewis.