There is no sustained recent work on either Harriet or Leon Lewis, although there is a brief post on the both at http://www.ulib.niu.edu/badndp/lewis_leon.html and another on Leon (whose real name was Julius Warren Lewis) at John Adcock’s Yesterday’s Papers site. Harriet has not benefited from the recent revival of Southworth and other American women writers. Most of the information about her in my London Journal book therefore came from the letters in the Bonner file in the New York Public Library. Brief obituaries of Harriet appear on 21 May 1878 in The New York Times (p.1), and The New York Herald (p.5) and a particularly affectionate one in the New York Ledger itself (4 June 1878, p. 4), largely devoted to reproducing extracts from Harriet’s last letter to her editor Robert Bonner, with whom she entertained a very good relationship.

Leon and Harriet had married in 1856 when she was 15 and he 23 with already a very colourful career behind him. Leon was to run off with another 15 year old soon after Harriet died, aged 37, of a botched gynaecological operation). The copious letters from Harriet and Leon suggest that Leon blusteringly carried on the business and squandered their money while she laboured over the novels – including some under his name.

Yet it is a letter from Leon to Bonner that is particularly interesting for its revelations of how American writers dealt with the transatlantic market.

9 April 1873

Dear Mr Bonner

We hasten to return by first mail the London letter and to reply to the question with which you accompany it.

You refused us the proofs 4 years ago, saying (in substance) to Mrs L. that if she were to have them she would be likely to give undue prominence to the thought as to how the stories would suit over there, etc. (which, by the way, was a mistaken estimate of her character).

We or you or all of us have consequently had some $1500 or $2000 yearly less income during the period named than we might have had. Mr Johnson, of the London Journal, and others have repeatedly written to us to this effect, but we never replied to more than one in ten, and then only to say (you having refused us proofs) that they were not at our disposal, etc.

The next thing in order of course were offers for original stories – i.e. for manuscripts – but a like answer was returned, although the offers made exceeded any sums that had ever been paid anywhere by anybody for anything in the line of stories.

And under this state of things it became a question with Sunday English publishers as to which of them would derive the most benefit from republishing from the regular Monday Ledger Mrs L.’s stories.

That is a race of printers of which we do not propose to constitute ourselves the time-keepers. We can do no less, however, than except Mr. Johnson, of the Journal, from the general condemnation. True, he reprinted the stories without authority and without paying for them – (since he could’nt [sic] have them for pay) – but he has done so under certain conditions which command attention from their rarity:

1st – He has given the name of Mrs L. and even given her a standing qualification of “celebrated American authoress”

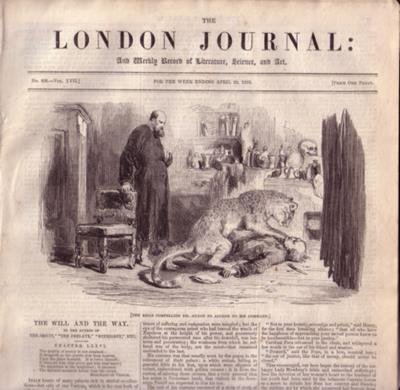

2nd – The London Journal is of ten times more literary importance and pecuniary value than all the rest of the story papers of the British Empire kingdom [sic] put together. The sum of $3,750,000 (£750,000) has been vainly offered for it to our own certain knowledge. [Here an unidentified extract from a book or magazine is pasted into the letter claiming the excellence of The London Journal. The sum Leon quotes is absurd]

3rd – During our stay in London in ’71, (as we must have told you upon our return) Mr Johnson called upon us at Morley’s [Hotel], offered us every civility, private boxes at theatres, invitations and introductions, etc. and upon the last day of our stay pressed upon Mrs. L a roll of bank [sic] of England notes, as an acknowledgement of the good he had derived from the stories, even in the face of sharing them with everybody else and under all the adverse circumstances – at which time he renewed his offers for proofs, as also for stories written expressly for him.

And now is this Mr Fiske [Amos Kidder Fiske (1842-1921), editor of the American fiction paper, The Boston Globe] more to you than we are that you should “aid and abet” him with the proofs you have so expressly refused to us, and so drag our names into a wretched squawk of a paper that could not possibly last three months, and during this period exist only in obscene contempt? After all you have been to us and we to you – after all we know of your heart and brain – we shall require your written declaration of preference in favour of Mr. F. before we will believe it!

Excuse scratches. We write in haste to catch the mail.

Ever yours,

Leon and Harriet Lewis

For all Leon’s protestations, The London Journal must have been supplied with advance copy of Harriet’s novels since 1869 (when Leon had first asked Bonner for proofs of her novels). Even more consistently than Southworth novels, Harriet’s appear in the New York Ledger and The London Journal at the distance of only a few weeks at most – anyone could work out that for that to happen advance sheets must have been sent across the ocean. No wonder Leon doesn’t want to be a timekeeper in what he calls the “race of printers” – Bonner no doubt had already made his calculations and come to the logical conclusions.

Leon’s also anxious to redefine the tag he claims The London Journal gave to Harriet. This was – he’s right – placed under her name in all of her novels until Edda’s Birthright, published in The London Journal and the Ledger 3 months after Leon wrote the letter transcribed above. But the tag of “celebrated American authoress” was only part of a longer notice. What the notice actually said was that The London Journal’s was “[t]he only edition in this country sanctioned by this celebrated American authoress”. The full tag was less a celebration of Harriet than an assertion of right.

The tag had been prompted in the first instance by the appearance of Lewis novels in The London Reader, a magazine run by no less than George Stiff, the former owner of The London Journal, from right next door. While almost all London Reader serials are anonymous and with altered titles and sometimes names of principal characters changed, it’s hard to trace the originals, yet it had carried novels with Leon’s signature in 1866-7 (The House of Secrets, 4 August 1866 – 12 January 1867) and in mid-1867, followed by one with Harriet’s, The Golden Hope. More recently, the Reader had somehow published The Hampton Mystery, a version of Harriet’s first novel in The London Journal, The Double Life; Or, The Hampton Mystery a fortnight earlier than the magazine which was published literally next door, The London Journal – which was, it seems, now forced into declaring that it alone had the only sanctioned edition. Since the original had been published in America at exactly the same date as in Reader, it was impossible for Stiff to obtain a copy and put it into print by anything other than advance sheets. Later, Harriet’s Tressilian Court (1871) will likewise appear in The London Reader a week before The London Journal’s version, and Lady Chetwynd’s Spectre (1873) at exactly the same time.

What’s happening here? One possibility is that Stiff was raiding the mail intended for his former magazine and now rival next door. While he’d certainly done this sort of thing before, there are other possibilities too.

It is clear from the Bonner letters that Leon was a spendthrift and a gambler. After Harriet had procured fame and a good deal of money for them both since first appearing in the Ledger in 1862 (aged 15 and already married to Leon), he had sunk very deeply into debt. Bonner, who was clearly very fond of Harriet, kept lending the Lewises money which she would pay back by writing several serials simultaneously for him under both her and Leon’s name (romances under hers, adventure stories under his): eighty-one numbers spread over five novels managed to pay off $6075 at half rates. It seems to me very likely that the Lewises sent The London Journal AND The London Reader – and quite possibly other magazines that I have yet to discover – advance copies of Harriet’s works to increase their already huge but always insufficient income.

What I’ve hoped to show in this and the previous blog posts is that in the cases of these three women – May Agnes Fleming, E.D.E.N. Southworth and Harriet Lewis – one cannot talk of “piracy” in the sense of a foreign publisher robbing an author. Two of the women had “exclusive” contracts with their American publishers which they broke quite legally by dealing also with publishers in Britain. Even when apparently straight piracy occurred, as with some novels by Southworth and Fleming, the writers still benefited from this in the end.

As we have come to realise more and more, nineteenth-century women writers were by no means all victims of a male publishing establishment. These three indeed, through translation, achieved a global circulation far beyond the transatlantic anglophone axis that I have focussed on here. In that sense they prefigure Hollywood by a good two generations – they are Hollywood’s grandmas indeed. The implications of that must await another set of posts.