Ouida, of course, from when her first story appeared in Bentley’s (she was just 18), had had to write for money. She knew where the power and money lay, and “mythical swelldom” was one place. In 1857 George Lawrence’s Guy Livingstone had appeared. It went through at least 6 editions by the mid-60s (the image is of an 1867 reprint by Routledge who evidently thought it worthwhile to print – and so establish copyright – in the US as well) and started the cult of the “muscular” hero. Even Dickens had to respond to it (see Nicholas Shrimpton’s excellent article on Lawrence and the “Muscular School” of heroes in Dickens Quarterly, 29: 2). Lawrence himself was given no less than £1,000 for his novels – a very high sum indeed – by his publisher Tinsley, and Tinsley it was who published in volume form Ouida’s first novel, Held in Bondage in 1863, a novel which combined the dashing muscular school with bigamy and sexual deception, themes newly marketable since Lady Audley’s Secret. Ouida though only managed to get £50 from Tinsley for the rights to publish it (though she did manage to negotiate that he should only keep the copyright for a limited period. Tinsley, rather unpleasantly, wrote that he could have got the complete copyright had he driven a hard bargain). Strathmore followed the same publication pattern, though published, after negotiations, by Chapman and Hall who were now to become Ouida’s regular British publishers. She managed to sell them the short-term copyright for just £75.

Even to get these small sums was an effort. Ouida, a half-foreign woman of 20 from Bury St Edmund’s with no real connections, had to work out a way to make money in the cut-throat male world of London publishing. Hers is in a sense “surplus” labour which has to make itself needed: she is an outsider who has to get in. The solution Ouida seems to have arrived at was to reflect back to power the image of itself it seemed to like. This is where the concept of parergy starts to become useful.

There is an oft-repeated story that Ouida used the conversations she heard between men at her Langham gatherings for her now most famous novel, Under Two Flags. But, as Jordan demonstrates in her chapter for Ouida and Victorian Popular Culture, Ouida’s knowledge of military life was derived from reading rather than from conversations with military men. Such textual knowledge is legible from her earliest publications, the short stories she had published in Bentley’s in the early 60s, several of which we can read today as devastatingly critiquing male pomposity exemplified by the soldier (e.g. “Little Grand and the Marchioness”). But they can also be read as simply amusing in their accounts of masculinity. That they concern “mythical swelldom” as opposed to what the male critics regarded as reality is key: Ouida doesn’t get it quite “right” i.e. she presents the men from the outside, exposing men’s little blind spots and tricks of evasion. At this stage, that doesn’t matter: for the critics these deviations – these failures to adhere to the powerful norm – are a laugh, “brilliant nothings”.

There is an oft-repeated story that Ouida used the conversations she heard between men at her Langham gatherings for her now most famous novel, Under Two Flags. But, as Jordan demonstrates in her chapter for Ouida and Victorian Popular Culture, Ouida’s knowledge of military life was derived from reading rather than from conversations with military men. Such textual knowledge is legible from her earliest publications, the short stories she had published in Bentley’s in the early 60s, several of which we can read today as devastatingly critiquing male pomposity exemplified by the soldier (e.g. “Little Grand and the Marchioness”). But they can also be read as simply amusing in their accounts of masculinity. That they concern “mythical swelldom” as opposed to what the male critics regarded as reality is key: Ouida doesn’t get it quite “right” i.e. she presents the men from the outside, exposing men’s little blind spots and tricks of evasion. At this stage, that doesn’t matter: for the critics these deviations – these failures to adhere to the powerful norm – are a laugh, “brilliant nothings”.

By the mid 60s Ouida’s prices had risen slightly. Over 1865–66 she received £6 per monthly instalment for Under Two Flags in the British Army and Navy Review, a monthly to which she had contributed a series of stories and non-fiction articles on military matters since July 1864. Just as Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret was left incomplete in its first manifestation as a serial in the twopenny weekly Robin Goodfellow, Under Two Flags was unfinished when the British Army and Navy Review folded in June 1866. Bentley had taken over the Review in December 1865 but failed to save it. He later refused to publish the novel in volume format on the advice of his reader Geraldine Jewsbury who concluded that ‘the story would sell but … you would lower the character of your house if you accept it’. Ouida wrote to another potential publisher, Frederick Chapman, a few months later claiming that the premature termination of the serial had left ‘military men’ waiting ‘with intense impatience’ to read the end. Her sales pitch to Chapman worked, for he published it as a triple-decker in November the following year. The American publisher Lippincott gave her £300 ‘by trade courtesy’ for his one-volume edition, and the continental publisher Tauchnitz brought it out in 1871. Three years later, Ouida was to sell her copyright outright to Chapman for less than £150.

This was to prove a costly mistake for, contrary to what has been claimed, the novel was initially only moderately successful. Its real success came in the 1890s when it sold in enormous numbers in cheap editions: Chatto and Windus, who bought the copyright from Chapman in 1876 as part of their vigorous expansion policy, were to print around 700,000 copies. Ouida got nothing from this. No wonder she was to write to her solictor in November 1884 that “Chatto & Chapman are two rogues who play into each other’s hands to keep down prices like the publisher in ‘Pendennis.’” Men still ruled the publishing industry, as they rule the wider media today.

By the 1890s, then, Ouida’s fiction has migrated downmarket. Interestingly, the penny papers do not treat her with the same attitude as the up-market expensive magazines and newspapers. On the contrary, for them she is “the leading female novelist of England” who has

“no rival in passionate eloquence, and the pathetic, emotional power by which she can change the lowly and the sinning into a glorified humanity, and lift up and ennoble and sanctify even the rudest nature by some one divine gem of supreme manifestation of sacrificial love” (Bow Bells 17 January 1890).

By this time, too, she had herself become comically wicked in that market. Unlike with the negative high-culture reviews of the 1870s and 1880s, this is surely a marketing ploy which positions Ouida as safely transgressive: her eccentricity is part of her scandalous appeal. One can have one’s desires enacted by someone else on the page without ever having to confess them as one’s own. Ouida is contained: once again we don’t have to read her seriously.

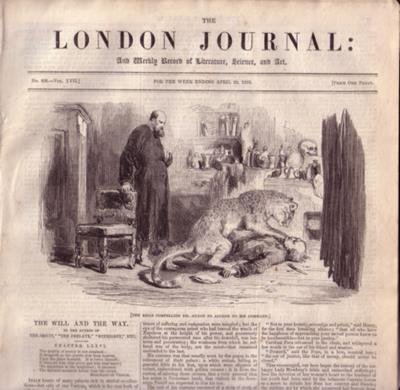

- London Journal 3 September 1898

- To return again to parergy.

Parergy is not dismissal de haut en bas by critics who claim to know better – it is not a weapon in cultural warfare that the powerful wield. It is a wheedling weapon of the disempowered, a demand to be heard which knows it will fail, an attempt to participate in power while knowing that the odds are stacked against it. Is this what Ouida does in her early work?

I don’t think Ouida’s imitations of the “Muscular School” fail in an unambiguous way so much as lay that school open to the possibility of ridicule or parody: they depart from it certainly, exposing its weaknesses and limitations and hidden assumptions. We are never allowed to forget that the hero of Under Two Flags is nicknamed “Beauty” and that he’s much more interested in his horse and his male friend “Angel” than in the heroine Cigarette or the paragon Lady Venetia or the actress he keeps (powerfully objectified as merely “the Zu-Zu” ) or his aristocratic mistress with the absurdly accurate name “Guenevere”. The women Beauty has a relationship with are all part of the appearance of masculinity. Even Beauty’s affair with Lady Guenevere is part of the system of masculine show: everyone knows about it and yet, in that complex game of respectability, at the same time they don’t. In any case, we are shown how this affair adds a potency to Beauty’s allure. How are we to take this exposure of the structuring of masculine power and image? Is it a flattering celebration or a merciless critique?

If the parergic can be found in Ouida it is gendered: excluded from literary-economic power, she mirrors back those representations of masculinity which generate it, while at the same time departing from them by the acuteness of her vision and anxiety as an outsider.

It is very different from the non-gendered, generic parergy I located in the 1840s. If anything, that kind can still be found in the penny paper reviews of the 1890s – think of the rather strained description of Ouida in Bow Bells, with its anxious determination to dazzle with rhetorical devices (most notably a tricolon) at all costs, or the anecdote in the London Journal which could be funny were its rhythms more bouncily organised, and were it less determined to excuse its subject as distracted.

Whether Ouida’s vision of men is parergic or parodic depends on whether we read it as undermining or supporting that masculinity. I think her version of muscular literary power in her early work walks a tightrope between parergy and parody: can we say with absolute conviction that her early work parergically supports its models while failing to live up to them or parodically undermines them by exaggerating and revealing? It does both, sometimes simultaneously but mainly, I think, it lurches from one to the other from sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph, page to page. The reader is in any case left uncertain, able to take from it in the end what she or he wants. Indeed, the ability of Ouida’s writing to have it both ways in terms of gender is one of the secrets of its success, and why it gives us such scope to write about this author and gender in what seems a mini-Ouida revival in the teens of the twenty-first century.

Over a hundred years after her death, we have started to find ways of reading Ouida again.