My thanks to Louis James for the gift some time ago of six volumes (bound as 3) plus 10 monthly numbers of Dicks’ English Library of Standard Works and, in anticipation, to Anne Humpherys’ ongoing research on Dicks and reprinting, to which this post is intended as a small contribution.

To both these remarkable scholars this post is dedicated.

As William St Claire has assertively reminded us on more than one occasion, the bibliophile connoisseur’s fetishisation of the “original” – the first – edition of texts has often occluded how reprints are actually more valuable in telling us about the cultural penetration of texts. The first edition is always to some extent “experimental” on the market. The publisher may have a good idea of who it will sell to and how how many copies will be shifted but the risk remains that he (for Victorian publishers were overwhelmingly male) may be wrong. Reprint editions still carry this risk of course, but to a lesser extent: the publisher already knows that the first edition or, indeed, the many previous editions, have sold and how quickly, and may even have evidence about who bought it, how the critics understood it, and so on. To that extent the risk is less. But reprints can also be aimed at radically different markets, as when Ouida is repackaged and sold in 6d form at the end of the century. The launch of a text in a new market may meet with considerable success, or it may not, so we cannot say with absolute conviction that reprinting involves less risk than first printing.

Anecdotally, one of the best selling series of reprints of the latter part of the nineteenth century comprised a periodical entitled Dick’s English Library of Standard Works. This was issued from one of the most successful London publishing houses of cheap fiction, John Dicks, on which there is almost no work at all outside an excellent volume privately published in 2006 by a descendant of the founder (Guy Dicks, The John Dicks Press, Lulu.com). Nonetheless, Dicks is certainly well known as a name not only to students of Victorian popular reading, to whom Bow Bells (1862-1897), Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper (1850-1967) and Reynolds’s Miscellany (1846-1869) along with Reynolds’s Mysteries of the Court of London (1849-1856) are all familiar, but also students of the Victorian theatre, for without the over 1,000 “Dicks Standard Plays” (published at a penny each between 1864 and 1907), many theatrical pieces would not be available to us at all.

John Thomas Dicks was born in 1818 and entered the London printing trade aged 14 or 15 “in a very humble capacity” (says the Bookseller in its obituary of Dicks, 3 March 1881). Around 1841 he became “assistant to P. T. Thomas, the Chinese scholar, who at that time was carrying on the business of publisher, printer and stereotyper to the trade on Warwick Square”. In the mid 1840s he started to be associated with G. W. M. Reynolds and in 1863 seems to have amassed sufficient capital to set up as a printer and publisher at 313, Strand, London, where he entered into formal partnership with Reynolds. After Reynolds died in 1879, Dicks bought his name and copyrights from his heirs for a very considerable annuity.

A major part of Dicks’ business, however, already comprised reprinting which he organised into several series, including “Dicks’ Complete Shakespeare,” and of course “Dicks’ Standard Plays” (see the first illustration in this post).

A measure of Dicks’s commercial acumen is suggested by his death (in 1881) at his villa in Menton, a resort in the south of France where the European and Russian nobility kept their winter villas. Dicks also had a large house, the Lindens (which no longer survives except in the name of a post-war housing estate), in the exclusive west London suburb of Grove Park, Chiswick (the location was not accidental, for not only does the nearby railway station go to Waterloo, from where Dicks could cross the river easily to his office, but census data reveal that his wife was born in Hammersmith, the next suburb east of Chiswick). His estate, valued at “under £50,000” – a very considerable sum – was left to his widow Maria Louisa and his sons Henry and John (see Ancestry.com. England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010). Clearly, cheap publishing and reprinting could be a very profitable business indeed.

The indefatigable journalist, gossip and bon viveur George Sala has an amusing anecdote at Dick’s expense, however, suggestive of how despite almost all authors’ interest in money, financial and cultural capitals might be inversely proportional to one another. It’s part of a longer story about his encounter at Nice with a “Captain Cashless” –“ middle-aged, good-looking, well-preserved… spent most of his money before he came of age; lived for several years on the credit of his credit; is a widower and spent every penny of his wife’s fortune” (Life and Adventures of George Augustus Sala, volume 2: 293). The Captain cannot understand where Sala gets his money from, but Sala feels he might

Sala lets us know that he can just toss off this profitable magic, turning the lead of his scribbling pencil into financial gold he can spend (and no doubt dispend) in Monte Carlo with his friend the glamorous rake. His methods of income generation and expenditure here seem to mirror one another in their low “real” value: both are fun, light, silly, worthless entertainments; good times, easily come by, easily left; in all Victorian senses, “fast”. In an analogue of the bibliophile connoisseur’s dismissal of the reprint as repetition, Sala dismisses his tales as the result of iterable alchemical formulae or repeated tricks of prestidigitation he has learned in the trade. Yet besides their illustration of the distance between cultural and financial capitals, such stories by their very comedy can hide from us the very serious business sense that lies behind them. It’s not that the fun is deceitful – on the contrary, without it there would be no commercial success – but that it is only one side of the coin.

- Dicks English Novels no 102: Reynolds, The Seamstress

Turning now more specifically to the reprinting side of Dicks’s business, in the 1870s a series of 6d volume-form reprints under the generic title “Dicks’ English Novels,” began to be published: they cost 6d and seem to have started as reset versions of novels originally serialised in Bow Bells. They also recycled the original illustrations. Many other novels were soon added, including, after the copyrights had been secured, works by G.W.M. Reynolds (see the image on the right for an example). In the end almost 200 titles were published in this series (more of which below). It was so successful a second series was begin in 1894.

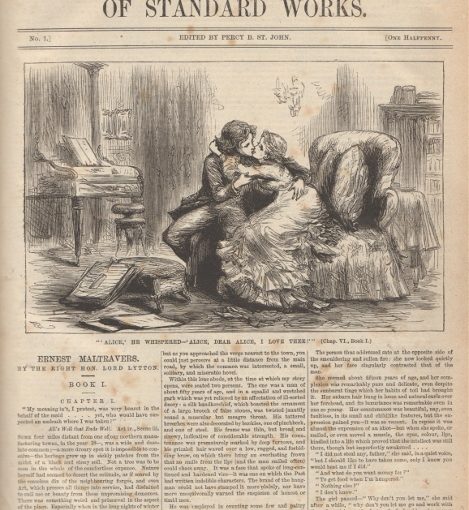

After his death, Dicks’s sons developed the reprint with Dicks’ English Library of Standard Works, a periodical consisting entirely of the serial re-issue of well-known novels. It came out in the usual 3 formats: weekly comprising 16 pages with four illustrations (costing 1/2d); monthly, consisting of the weekly numbers for the month costing 3d, in orange covers comprising mainly adverts; and in volume form of 416 pages plus title page and frontispiece costing 1/6. “Dicks’ English Library” was a quarto – the same size and format as most 1d or 1/2d periodicals such as the London Journal, Bow Bells or Reynolds’s Miscellany – and was first published on 27 June 1883. It ran for 38 volumes right up to 2 March 1894 whereupon (just as with Dicks’ English Novels”) a new series was started. Percy B. St. John was the editor of the first few volumes (on whom see a subsequent post).

A typical announcement for the periodical can be seen here, justifying its publication not (of course) in commercial terms but in those of Whig public utility that could have come from the 1830s. (The following is from the Pall Mall Gazette, but similar adverts were placed all over the press)

Besides the list of authors above and the more obvious suspects in the world of Victorian popular fiction – G.W.M. Reynolds, Bulwer Lytton, Charles Lever, G.P.R James, Captain Marryat, Paul de Kock and Dumas ‑ also included were Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (and Percy Bysshe’s Zastrozzi, both illustrated by the well-known illustrator Frederick Gilbert – Shelley’s complete “Poetical Works” are published later in the series), Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda, Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Hawthorn’s Scarlet Letter and Godwin’s Caleb Williams. Most intriguing (not least from the point of view of copyright) is the heavy presence of Dickens, including, later on, Dombey and Son as well as numerous individual tales.

The reissue of these texts cannot be taken to be an unalloyed index of popularity amongst the readers of cheap publications. The Dicks firm is clearly aiming at respectability and the aspirational reader keen to build up that sign of cultural capital, a “library” – the page numbers of each weekly and monthly number are incremental, asking the reader to keep them so as to build up the volume. The Shelley poetry may have been suggested by the revival of interest in him amongst the literati with Rossetti’s Moxon edition in 1870: it is a mark of what the public should aspire to rather than of already extant popular demand. Publication in this form is no indication that any particular author was read unless the author’s other works are also issued, and even then business reasons other than consumer demand may have prevailed – for example, copyrights might have been bought as a job lot in advance, and accordingly had to be exploited, or there were vacant pages that had to be filled with works whose copyright had lapsed. One also has to take into account what other works were serialised with, before and after any particular text, for it may be any or all of those that carried the periodical through rather than the particular text one is looking at.

What one also has to do is try to establish the publishing history of a series. Adverts are always useful for this and one on the monthly cover of “Dicks’ English Library” (October 1888) shows that by then 197 titles had been published in the “Dicks’ English Novels” series for example. The missing titles were presumably exhausted, but they can be identified by reference to other adverts elsewhere, either in other publications or earlier in the series (cf. the following with the first image of this post).

The history of the Dicks reprinting series has yet to be mapped: even a basic bibliography is lacking. After that is done, one of the many questions that can be answered concerns the relations of synergy between the various publication forms: for example, how far did the English Library reprint works previously available in the volume-form English Novels series? More complex questions can also be addressed, including the implications for the history of the canon, its creation, modification and its reception – if any – of the publishing choices of this financially rich but status-poor house. The use of a garland of portraits of authors as a frontispiece for “Dicks Standard Library” suggests the prioritisiation of some authors over others: this prioritisation needs to be charted and compared to the number and positioning of authors actually published (a front-page author is lent greater prominence than one whose work starts on a middle page, for example).

These, and many other questions about this most interesting publisher, still await answers, and we look forward to them in due course.