On Sunday 29 September some of GMI’s staff and alumni took the opportunity to explore the River Thames from the City to Southend and the mouth of the River Medway, including a unique close reconnaissance of the new London Gateway port which is due to open in November 2013, aboard the Glasgow-based steamer Waverley.

Waverley, completed in 1947, spends her summers cruising on the Firth of Clyde into areas of spectacular natural beauty. She also spends spring and autumn sailing in other areas including south-west England (Dorset and Devon), the Bristol Channel, the south coast of England and the Thames estuary. Since 1974 she has been owned by a registered charity (Waverley Steam Navigation Company) on behalf of the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society (PSPS), itself a charity, and operated by Waverley Excursions Ltd, a subsidiary of WSN. She is described as the ‘World’s last Sea-Going Paddle Steamer’, and sometimes cruises out of protected estuarine waters and across more open seas, including up the east coast to Harwich, Ipswich, Great Yarmouth and Southwold. She sailed across the Channel to commemorate the sinking of her predecessor, built in 1899, during the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation. Being a paddle steamer she is extremely stable, but she only has one giant engine, which means she cannot turn very tightly by contra-rotating the paddles. But she is manoeuvrable enough, even for the relatively constricted waters of the Pool of London.

http://www.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-

And the engine is open for all to see, her immaculate, slightly greased metallic silver connecting rods, carrying the energy from the pistons, pumping rhythmically to turn the crankshaft in a stimulating display of raw power.

On that special Sunday she left Tower pier at 10.00 hrs sharp with about 200 passengers aboard. She sailed west, towards London Bridge, swung round above the site of the old Roman bridge, and headed out under Tower Bridge which opened for her. The Waverley cruise has become something of a GMI tradition over the last five years, but the prospect of a close encounter the new mega-port on the verge of completion made this year’s excursion particularly timely. Aboard were Chris Bellamy, on his first Waverley trip accompanied by Jos McDiarmid, a friend specialising in antique prints and a qualified London tour guide, the usual suspect Dr David Hilling, a world expert on ports, Richard Scott, and graduates and continuing students from the Maritime History MA including John Allan, John Mann and his son, Robert Milburn, Tim Carter, his partner Anne and friend, and Peter Jarrett, plus a representative of the new Maritime Security MSc, Leo Balk, who is a former Commander in the US Navy.

The weather was overcast and quite stormy, and on the wider river there was a strong wind which made using maps challenging, but blew any cobwebs away. After Tower Bridge, Brunel’s Thames Tunnel and Canary Wharf, Greenwich came into view.

Soon afterwards there was a good view of the Emirates AirLine cable car, which is a spectacular sight but might be more useful if it went somewhere, either to the

Excel Exhibition Centre, further east, or directly to London City Airport. But maybe that was just a ‘bridge’ too far.

Then came the Thames Barrier, designed to defend the Capital against the power of the sea. One of the barriers was obligingly raised in ‘defensive’ mode. The Thames Barrier, which has been operational since 1982, has a finite life, and will need to be replaced at some point, but a March 2009 study suggested that it would last decades longer than the date of 2030 when its designers thought it would have to be replaced. In part, this was because they had apparently overestimated the effects of climate change. The barrier was designed with an allowance for sea level rise of 8mm per year until 2030, which has not been realised in the intervening years. The Environment Agency have no plans to replace it before 2070 and a decision on its replacement, which might be further downstream, therefore needs to be made in the middle of the century.

The route so far can be traced on the Google Earth photo, below. The next part of the trip was more revealing. The Thames Barrier is not the only London flood defence by any means. Two kilometres from the eastern end of London City Airport, ad Ordnance Survey grid 456817, on the left of the river (to Port), we saw the imposing and intimidating outline of the Barking Creek barrier, which can be dropped as a giant guillotine to seal Barking Creek against the same tidal surges from the North Sea that the Thames Barrier is designed to thwart.

Google Earth, adapted and annotated by author

And then, further on, on the ‘right bank’ of the river (always seen from the direction of flow, remember…), the Dartford Creek (River Darent) tidal barrier. OS grid 541778:

Four kilometres beyond this point the Waverley passed under the Queen Elizabeth II (QEII) bridge, which carries the southbound carriageway of the M25 orbital road southward. The northbound carriageway passes through the Dartford tunnel a little before. The central point of the bridge is at OS grid 570764.

The best shot of the bridge is probably taken from further east, as shown below. The traffic is therefore passing southward, to the left, with the south bank on the left and the north on the right of the picture. The overall position of the bridge can be seen in the adapted Google Earth view, which follows.

Google Earth, adapted and annotated by author

After Tilbury docks, Waverley passed Tilbury Fort, skulking behind its earthworks, and very difficiult to see (OS grid . After the Dutch raided the Medway in 1667, King Charles II ordered a fort built here to defend London. It was designed on the latest lines, following the schemes of the great French military Engineer Sebastian le Prestre de Vauban. It was built by a Dutchman, Sir Bernard de Gomme, and its fearful pentagonal geometry incororated the latest ideas in 17th century fortification. Originally the fort, designed to withstand a serious assult from the landward side, was combined with batteries along the northern shore of the river, as shown in the artist’s impression of it in the eighteenth century, below.

http://www.englishheritageprints.com/tilbury_fort_j910014/print/674682.html

http://www.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/content/images/property-defaultimage/tibury_fort_lead_image.

Beyond Tilbury Fort we rounded the bend in the river, heading north again into Lower Hope Reach. The new Thames Gateway port, buyilt on the site of the former oil refinery at Shellhaven, which closed in 1999, came into view. As you can see from the air view, the new port is vast. Its shape is quite distinctive, and it is easy to reconcile the artist’s impression of the completed port with the air view.

Google Earth, adapted and annotated by author

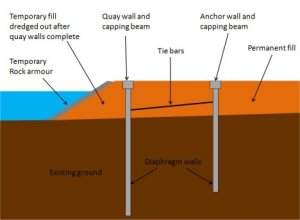

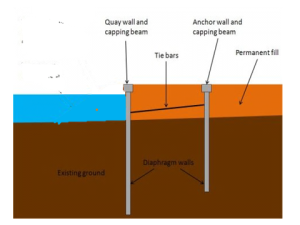

The Waverley moved close in to the north bank to give us a good view. As we slipped past huge excavations were still underway. The technique used to construct the quay wall which will also support the tracks which carry the huge cranes is not new but has not been much used in the UK previously. The shoreline was build out extensively, so that the quay wall could be installed below ‘dry land’ The fill behind the quay wall then becomes the fill under the quayside areas.

The two lines of quay wall also double as the support for the enormous quayside container cranes so the capping beams have the necessary rails and infrastructure cast into them. Once the quay wall, anchor wall and tie bars are complete, the fill in front of the quay wall is dredged out leaving the quayside complete. The cranes run on tracks that are 35 metres (115 feet!) apart, giving an idea of their enormous size. The first phase of the quayside wall in 1,250 metres long.

http://www.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://constructionetc.files.wordpress.com/2011/

As above, adapted by author.

One ship was already moored at the port, although it does not formally open until November. And two weeks before, on 16 September, it was reported that THE 10,062-TEU Zim Rotterdam, had diverted from Felixstowe to DP World’s London Gateway port for repairs after a fire aboard had consumed 20 containers. Industry sources said Felixstowe would not accept Zim Rotterdam because the vessel would tie up berthing space for a prolonged period, but Felixstowe officials were not available for comment. Instead, it was offered a haven at London Gateway, which will not open until later this year. As a result of an unplanned delay, London Gateway port agreed to accommodate the vessel at short notice. Three weeks before, ago, the master had reported a fire in 20 of its containers while en route from Malaysia to Djibouti. The AIS vessel monitoring system showed that Zim Rotterdam was located off Cherbourg when the new London Gateway destination was determined.

As we passed the new mega-port the size of the cranes on their 35-metre wide track could easily be appreciated.

London Gateway comprises a large new deep-water port, which will be able to handle the biggest container ships, as well as one of Europe’s largest logistics parks, providing effective access (by road and railways) to London and the rest of mainland UK. The complex will make use of modern technology to increase productivity and reduce costs for shipping lines and the logistics industries. It will significantly increase the ability of the Port of London to handle modern container shipping, and help meet the growing demand for container handling at Britain’s ports.

DP World, a Dubai-based company, received Government approval in May 2007 for the development of London Gateway. The proposals were identified by former prime Minister Gordon Brown as one of the four economic hubs essential for the regeneration of the Thames Gateway. The 2007-10 financial crisis created problems for DP World’s owners Dubai World. However, in January 2010, DP World was given the go-ahead for construction of the port

London Gateway port will include a 2,700-metre-long container quay, with a fully developed capacity of 3.5 million TEU a year. It is close to the major shipping lanes serving north west Europe and will increase national deep-sea port capacity for the UK. At present, the ports of Felixstowe and Southampton are the first- and second-largest ports by container traffic in the UK, respectively, with the Port of London third. There are a number of other smaller container terminals nearby, but the development will dramatically increase the capabilities of the Port of London in handling modern container shipping. DP World has said that high-quality architecture, sustainability, and high levels of security and management will be key features of the park and will create an attractive environment for occupiers

DP World is planning to invest over £1.5bn to develop the project over a ten to 15- year development period. It says (well, it would, wouldn’t it?) that London Gateway will deliver about 12,000 new direct jobs, benefit the local and regional economy, and assist the government’s regeneration initiative. In addition, there will be over 30,000 indirect and induced jobs.

Our intelligence mission complete, and by this time very windblown, we repaired below. The Waverley served an excellent Sunday roast, and the stability of the ship was noticeable as she ploughed through a very choppy Thames Estuary towards Southend. Some of the passengers disembarked there, but the Captain warned that he could not guarantee to get back at 17.00 hrs to pick them up. At sea, no plan always survives contact with the elements. We then headed south, into the estuary of the Medway.

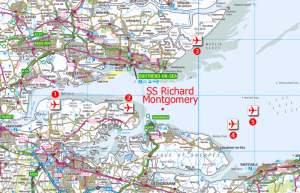

I was still below when we passed by the wreck of the Richard Montgomery, a US Liberty ship that had gone down in 1944 with several thousand tonnes of ordnance on board. On 20 August 1944, it dragged anchor and ran aground on a sandbank around 250 metres from the Medway approach Channel, in a depth of 24 feet (7.3 m) of water. Liberty ships of this type – ‘general dry cargo’ – had an average draught of 28 ft (8.5 m). However, the Montgomery was trimmed to a draught of 31 ft (9.4 m). As the tide went down, the ship broke its back on sand banks near the Isle of Sheppey 1.5 miles (2.5 km) from Sheerness and 5 miles (8 km) from Southend. The salvage operation began on 23 August 1944, using the ship’s own cargo handling equipment. But the next day the ship’s hull had cracked open, causing the bow end to flood. Attemp[ts to salvage the lethal cargo continued until 25 September, when the ship was finally abandoned. Subsequently, the ship broke into two separate parts, roughly in the middle. Some 1500 ‘short tons’ (the standard US measure for weight of ordnance), or 1400 tonnes, were left on board.

The Richard Montgomery is a potential hazard to developments in the Thames Estuary. The map below shows the position of the wreck vis-à-vis some planned developments – the various estuary airports beloved of, among others, London Mayor Boris Johnson.

In 1970 the BBC reported that the 1500 short tons – 1.5 kilotons – of explosives could, if detonated produce a 3,000-metre high column of water and a five metre tidal wave that would engulf Sheerness (population then 20,000). By 2012 estimates of its possible effect were less sensational, but a one metre tidal wave might still result. However, in 1998 The Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) had said that as the fuzes would probably have been flooded for many years and the sensitive compounds were all soluble in water,‘ this is no longer considered to be a significant hazard.’

At least the wreck is clearly visible. Given the weather conditions, Waverley did not pass very far down the Medway, just past the Swale, the stretch of water which separates the Isle of Sheppey from the mainland. She got as s far as Saltpan reach, south of the jetties and power station in OS grid square 8674, before turning round.

On the way back the Waverley passed east of the wreck site, before turning west. The Richard Montgomery’s three masts are clearly visible.

The light was now beginning to fade and we repaired below for a while longer. The Waverley did make it back to Southend, picked up some passengers, and then headed back into London. As darkness fell around 19.00 we headed back on deck and the lights came on. The imaginative use of lighting can utterly transform a landscape. The Thames Barrier and to O2 were cleverly illuminated. Beyond the O2, from the Royal Observatory, the Greenwich Meridian, the centre of the world, dividing east from west, was marked by a green laser pointing slightly upwards into the sky. Unfortunately it would have needed a long exposure to capture this beam of light, and I missed the shot. But an idea of the effects can be obtained from the kaleidoscope of colour bathing the O2, below.

The Waverley passed on, under Tower Bridge, and docked at 20.45. It was a great day, and a marvellous opportunity to behold London’s new great port.

I could not help wondering what would really happen if what remained of the Richard Montgomery’s cargo were detonated all in one go. I am sure that Maybe a future Mayor of London, inaugurating an estuarine airport, might have the opportunity to find out. Mind you, I am puzzled by the need to build vast concrete runways. Why do we not go back to sea planes and flying boats, which could land and take off in this vast area with far less infrastructure investment. And bring back more civilised travel into the bargain. But a future Mayor might still want to press the button, just for fun.

Hey! That gives me an idea…

Chris Bellamy

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs by the author.