Why is it that the most beautiful parts of the earth are often identified with recent war, atrocities, brutality and horror? Sierra Leone is one. And besides its stunning beauty and wealth of resources, it also has one of the most evocatively descriptive names of any country in the world. ‘Lion Mountains’, from the Portuguese Serra Lyoa, after the Portuguese explorer Pedro da Cintra sailed by in 1462 and saw, in the mountains on what is now the Freetown Peninsula to his east and north, the shape of a crouching king of beasts. Not everyone can see it that way, but then, we do not know what substance what he was on at the time…

It is more than eleven years since hostilities formally ceased here on 14 May 2001. The signature of the Cessation document at the Mammy Yoko hotel, headquarters of the UN Advisory Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) brought to an end a civil war that had lasted for a decade, since 1991. Like all peace processes, it had stuttered and veered off track: the Lomé (Togo) Peace Accord of July 1999 had established a ceasefire and an amnesty for war crimes and ghastly atrocities. But the fighting and atrocities were far from over. The Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), who had been allies, fell out and in May 2000 the RUF started taking UN Peacekeepers hostage. Up to then UK involvement had been minimal and the UK had been implicated in the involvement of two private security companies: Executive Outcomes, which had supported the Sierra Leone government in 1995-96 and Sandline, which had supplied logistics and intelligence for the previous peace-keeping force, ECOMOG, in 1997-98. Both these private security companies appeared to have an ulterior motive – they had also been linked to diamond-mining in the country.

In 2000, nearly a decade into the war, the British Government sent a 1,000-strong task force into its former colony to support the UN, guard Freetown’s Lungi airport and evacuate its own nationals. After an efficient operation led by Brigadier David Richards, who later became Chief of the Defence Staff, they withdrew, leaving a small training force. In August the West Side Boys, a splinter group now allied with the RUF, captured eleven British soldiers who had been training local forces. Among 500 UNAMSIL personnel who had been captured earlier was an unarmed observer, Major Andy Harrison of the Paras, who later became one of my students at the Defence Academy of the UK. The RUF held him for eleven days, during which he was threatened with death and beaten occasionally. Then they released him and some fellow hostages into the hands of Indian troops who remained surrounded and dug in. In September a British operation freed the hostages, and relieved the Indian troops along with Andy. In the meantime, the British had also fought off two RUF attacks on Lungi airport. This all raised their profile and restored their honour. Two meetings in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, in 2000 and 2001, began to set a more lasting peace and the final ceremony was held in February 2002. The process of ‘Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration’ (DDR) began and was complete by 2004. In the same year a UN war crimes court, the Special Court of Sierra Leone (known locally as ‘The Special Court’), began trying senior leaders from the RUF, AFRC and other factions on the losing side. The last armed international peacekeepers left in 2005 but a small British-led International Military Advisory and Training team (IMATT) still remains.

The abiding image of the fighting is probably that of child soldiers, of whom an estimated 10,000 were abducted and forced to fight, and the same number who were taken as sex slaves and forced labour. And of child mutilation. Cutting of hands, lower arms, feet and lower legs. Eleven years on those children are young men and women. Now, on Lumley beach, a stunning three-mile stretch of white tropical sand and one of Sierra Leone’s many superb beaches, you see amputees playing football. The competitions have attracted international attention and must place Sierra Leone in a strong position for developing paralympians. Outside one of the four or so St Mary supermarkets in the city, there were more amputees, raising money to train, wearing blue ‘Team GB’ tee-shirts. In spite of the horror, there is hope. It is humbling.

I flew into Freetown International Lungi airport on the direct 7-hour thrice-weekly BA flight from Heathrow at 05.15 on 26 February. My hosts were Save the Children International. As you can see, given what has been going on here, they have quite a job on their hands! You can get a visa on arrival at the airport but I had already obtained one from the High Commission in London. Bai-Bai, who met me, said he would have to ‘make a phone call to the ‘CD’ – Country Director – to let her know I had arrived.

The next stage was terrific. Lungi airport is on flat ground north of the Sierra Leone River estuary, while Freetown is on the hilly south side. Out of the airport terminal, I checked in for the Hovercraft flight across the five miles or so of Estuary to Freetown. One day there will no doubt be a fast motorway linking the capital with its airport, but that would be rather a pity. It was still dark and we were driven down a bumpy, winding dirt track to the beach, and a shelter. Across the estuary the lights of Freetown were just visible, fading and reappearing as the pre-dawn mist shifted. Behind us, there was full moon, glowing a strange orangey pink, more like the planet Mars. This must be the result of the harmattan wind, I thought. At this time of year – November to February – the harmattan brings dry, reddish Saharan sand, blotting out and colouring the sky and carpeting the land with dust.

We waited, not far from our luggage, carefully tagged, by the landing point. Make sure you hang on to all baggage receipts, or you won’t get it back! The landing point, a rocky slope, was easy to determine. There was a red neon light on one side, and a green one on the other. Port and starboard – from an incoming hovercraft’s point of view. I explained this to some visiting aid workers, who were duly impressed (enough – Ed.!) Sierra Leone remains very aid-dependent. About half of the country’s economic growth in the late 2000s was driven by donor money, and the numerous aid agencies continue to prop up the economy. Then, very quickly, like Kipling’s tropical sun, coming up ‘like thunder, out of China, ‘cross the bay’, the sun rose behind us, too.

At about 07.00 the hovercraft appeared. Bright yellow and black, and, as one the Water Aid workers explained, a former Isle of Wight Ferry, now a long way from home! There are also boats which do the crossing, and only boats operate at night. This was the first hovercraft transit of the day. The hovercraft made its first run, powering forward propelled by two huge propellers at the stern. But the hovercraft had not built up quite enough momentum. She got most of the way up the rocky slope, then slid back. Oh dear! So she reversed, turned round in the water, spraying sea everywhere, and headed out to sea again. For a moment I was worried that she was deserting us. Then she came in a second time. Everbody got well back in the shelter as the exiled Isle of Wight sea monster came powering in, like an athlete going for an Olympic Gold in the long jump.

This time she made it. Passengers and baggage for Lungi airport came off, and we got on, sitting in the tasteful zebra-pattern seats. The crossing takes 20 minutes, and on the way we watched a ‘welcome to Sierra Leone’ video, which was very informative. Sierra Leone was the hub of much of the West African slave trade and the descendants of slaves in some of the southern US states, including Alabama, largely trace their origins to one of the Sierra Leone ethnic groups. On the southern, Freetown side, the hovercraft’s berth was more conducive, and the craft came to a halt first time. Waiting in the baggage hall there was a blonde lady, radiating a Helen Mirren-like air of quiet authority. Now – this could only be the Save the Children ‘CD’.

I was intrigued by the provenance of the hovercraft, and I initially assumed – quite wrongly, as it turned out, that she was a creation of the 1960s, remembering that Sir Christopher Cockerell had invented the hovercraft in 1952 and that, with a speed impossible today, commercial hovercraft services to and from the Isle of Wight had started in 1962. I initially thought she was an SRN-6, But the round propeller guards belied that. The SRN-6 has angular propeller guards. In fact she is the SRN-6’s successor, an earlier version of the Hovertravel Freedom 90 which is still in service on the Isle of Wight route. The Freetown hovercraft is an AP1-88, first tested in 1982, built by Hoverwork, the British Hovercraft Corporation (BHC), and the National Research Development Council (NRDC). But I am no train-spotter…

‘Diamond Airlines’ is appropriately named. Sierra Leone is a rich source of diamonds, as well as gold, rutile, iron ore, zircon, uranium – and offshore oil. Diamonds were first discovered here in the 1920s, and in 2006, after the peace, $140 million worth were exported. Exports fell because of the global economic downturn but rose again to $109 million in 2010. But the country is also shaped like a diamond – pretty much like the diamond on the hovercraft ticket. The point at the bottom lies at about 7o north, 11o 30’ west. Freetown lies near the top of the flat west face at 8o 30’ north, 13o 10’ west. One of the advantages of that, of course, is that the country is on the same time zone as UK, not far from our very own Greenwich Meridian. So no jet-lag here!

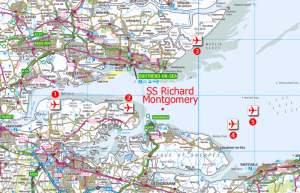

From a GMI point of view, Freetown is exceptionally important because it is the deepest natural harbour in West Africa. It is free of sand banks and has long been an important trading entrepôt and refuelling stop. Freetown lies south of the Sierra Leone River estuary, but the broad expanse of water is referred to by the locals as ‘the river’. To the south lie the Peninsula Mountains, the Serra Lyoa. John Hawkins was the first known Briton to come here, in the 1560s, to buy slaves. The British built a fort on Bunce island, from which an estimated 50,000 slaves were exported up to 1808. The French destroyed it in 1702 but it was rebuilt and occupied by the Dutch and Portuguese.

But Freetown’s position as the capital of Sierra Leone and its name owe as much to the end of the slave trade. By the end of the 18th century pressure against slavery was growing in UK and a number of slaves had already been freed. There were also American slaves who had escaped their American owners and fought for Britain in the American war of Independence. The proportion of black people in London was therefore as high as today, with the latter, and also because as it was fashionable to have black servants, and some of these had fallen on hard times, though ‘free’. In 1786 a contingent of freed slaves from UK and British North America (Canada) – the US did not abolish this appalling abuse of human rights until 1863, as we all know – arrived in what became, in 1787, the ‘Province of Freedom’ – later Freetown. The first freed slaves, many from cold Canada, had a miserable time and many died in the malarial conditions of the swampy coast. But the new colony – limited to the coast – survived and prospered. Britain finally abolished the slave trade in 1807, which triggered the growth of Freetown, as it now became. The following year, 1808, ‘Freetown’ became Britain’s first Crown Colony in tropical Africa.

The Royal Navy now found itself in a quandary. Its mission was now to intercept slave ships under other flags and free the slaves. But where were they to take them? Freetown. With war against Napoleon still underway, 6,000 freed slaves were brought to Freetown to enlist in the British forces – too many for the small settlement to handle. So the British farmed them out to neighbouring villages. This also began a reluctant process of colonising the littoral. By 1864, when the final slave ship was intercepted, 50,000 freed slaves had been brought to the settlement. With the deepest natural harbour in West Africa, Freetown was also an important Naval stopping and resupply base, and remained so even after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. It remained so in the First and Second World Wars as well, and in the latter the Freetown Squadron played an important role securing transatlantic supply convoys for North Africa against U-Boats. At the Schwerpunkt between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Guinea, Freetown could be a major factor in maritime security in the next century.

Today Freetown remains a bustling port. There is nowhere with the natural advantages it enjoys anywhere in West Africa. From the CD’s terrace she can see a constant stream of ships plying the ‘river’: container ships, tankers, dry bulk carriers… Swooping above are African Harrier Hawks (Polyboroides typus), which are common across all west Africa, from Senegal across southern Mali to the Central African Republic and down to Congo Brazzaville. These raptors have a 1.6 metre wingspan and their bodies are 60 cm – two feet – long. Charlie, the CD’s three month old kitten, is currently happy to play in the house and on the covered terrace. Probably a good thing. To one of these raptors, Charlie, at the moment, would be a tasty lunchtime snack.

In spite of the appalling history of brutal horror, this country is amazingly alive. Compared with the grungy, crouching creatures hiding in their hoodies who adorn London, these people, who are desperately poor, stride proudly upright, the men in ornate, tailor-made shirts, the women with the same carriage as when they carry baskets on their heads, in elegant dresses glittering with ornament.

A huge amount of work is underway to revolutionise the country’s infrastructure. Some impressive new roads – dual carriageways – are being built, with Chinese help in and around Freetown and South Korean help up-country. There are two ‘seasons’ here: wet (May to October) and (now) dry – or baking (November to April). In the wet season the rain is torrential and pretty constant, and the deep culverts and metre-deep drainage channels, crossing under and on either side of, the new carriageways were really impressive.

But, at the moment (March 2013), power is the big issue, certainly in Freetown. Not the political sort, although they are related, but the supply of electricity. In November 2009, with great fanfare, President Koroma announced the opening of the Bumbuna hydroelectric power station on the dam of the same name, a graceful creation of Italian engineers. Bumbuna is 100 miles inland from Freetown, up the Seli or Rokel River, which flows roughly west into the Sierra Leone River estuary, and is virtually in the centre of the country. It had been nearly forty years in the making. The plans were unveiled in 1975 but construction ceased from 1997 to 2005 because of the civil war. The 400 metre long Bumbuna dam was designed to solve, first, Freetown’s power problem and, with Phase II, Sierra Leone’s. Phase I, completed in 2009, has two 25 MW Francis turbines, capable of delivering 50 MW in total. Phase II, due for completion in 2017, will increase this to 400 MW.

According to the official statements, Bumbuna could supply all Freetown’s power needs. But the power distribution network was so damaged during the war that Freetown can only handle half of the power that Bumbuna can produce. That corresponds roughly with the observed fact that mains power was available for about half the time. But in recent weeks the mains electricity supply to Freetown has hardly worked at all. Generators, designed to provide power the rest of the time, and as emergency standbys, have been operating almost permanently. So they are starting to break down…

A Presidential statement apparently said that the power outages were because one of the two turbines was broken, and would take a year to fix. Given that the distribution network could only handle half the power produced anyway, one turbine should be quite sufficient, so this does not add up. I suspect that the problem lies with the decrepit distribution network. President Koroma was recently re-elected on the promise of restoring electric power. If he does not get his act together on this one soon, he could be committing political suicide.

The Bumbuna dam

Until such basic issues are sorted out, Sierra Leone will struggle to attract business and tourists. It has stunning resources and has a spectacular, hilly landscape, quite different from the low-lying swampy coast of much of West Africa. And it has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world. The original Bounty bar advert was filmed here in the 1960s (when it was still a British colony). On my fourth night I headed, with the CD, along Lumley Beach. The sun was coming down fast over the sea, first ultramarine, then turning to black, with the white surf spray pounding onto white sand. The currents are strong – this is the Atlantic Ocean – and swimming would be risky. But when we reached the Atlantic Restaurant at the far end of Lumley Beach, we sat looking out at the dark mystery of the Atlantic, under coconut palms blowing in a refreshing, cooling breeze. Next stop – South America. The beauty of the place cannot fail to impress.

We looked at the menu. One great thing about Sierra Leone is that one is not oppressed by freedom of choice. The choice is limited, but everything is very good.

‘The Barracuda’s OK here’, said the CD…

It’s an ill-wind …

Chris Bellamy, Director, Greenwich Maritime Institute