Gerhard Kristandl

Remember, remember the time before the 30th November, back in 2022? Remember how your assessments worked for many years, as they (seemingly) helped measure your students’ learning, and how academic misconduct was mostly copy-pasting from existing sources and essay mills?

The launch of ChatGPT – for many synonymous with “Generative AI” – has caused a veritable sea change not just in education, but society. When the public gained easy access to tools that could write, summarise, and analyse with seemingly astonishing fluency, the media was quick in producing sensationalist headlines announcing the death knell to teaching and learning. Such doomsday scenarios aside, generative AI became an invisible collaborator in our classrooms, whether we invited it or not. For those of us in higher education, this was nothing less than a pedagogical earthquake. “Now all students will cheat” was one of the most common statements I heard from colleagues across in discussions, workshops, and conferences that quickly sprung up in early 2023.

But is the end of assessment near? Let me pose a provocation following a discussion I heatedly conducted with myself over two years ago: if AI can complete my “traditional” assessments to a satisfactory level, am I really still assessing what I meant to assess? Early on, I understood AI as a technology that would be ubiquitous (not “inevitable”), so rather than treating it as the enemy at the ivory gates of education, I began to see it as the catalyst desperately needed to finally do that much-invoked “rethinking” of my assessment practices.

*Full disclosure: Some images in this article have been generated with Adobe Firefly, trained on Adobe’s own, fully licensed stock images. Prompts provided in alt-text of each image.

The authenticity crisis is real

The validity of ‘traditional’ assessments is under unprecedented pressure when submitted work no longer reflects assured learning and students’ own capabilities (Dawson et al. 2024). ‘Classic’ essays and short-answer questions could now be completed with minimal human input, eroding trust in academic integrity (Cotton et al., 2023).

But banning AI or relying on detection tools isn’t viable (Perkins et al., 2024). These tools are unreliable, prone to false positives, and can disproportionately affect non-native speakers. Moreover, students are already using AI, often unguided, while workplaces increasingly expect AI fluency (Mayer et al., 2025). Refusal might thus not serve our students well – and said students may start asking if and how AI is used in supporting their learning and their future work practices.

A different approach: process over product

Instead of fighting AI, I gradually changed how I assess. I moved away from a ‘final product only’ focus toward tasks that unearth process, exploration, and decision-making, putting process on par with product. This was the most significant ‘sea change’ in my own assessment practices and – clearly – did not happen overnight; it was an iterative journey, with many steps forward and back, lessons learned and continuous student feedback on what works and what doesn’t. In other words: a teacher’s daily bread of rethinking, reflecting, and changing.

Below, in a nutshell, follow some approaches that I have applied in my own practices and that you may find useful in your own assessment ‘rethinking’.

1. Scaffolded submissions and reflective documentation

By scaffolding submissions, students work alongside and submit interim steps, not just a final polished product, creating breathing space for feedback, allowing for mistakes and interim revision, and helping students build confidence in their own learning. Through reflective documentation, students develop metacognitive awareness. Educators’ guidance matters enormously here – students often need support to move beyond description to genuine reflection, so they start to see themselves as thinkers, not just deliverers of text.

2. AI Journey assignments

AI Journey assignments make the invisible visible. Students specifically document how they used AI – what prompts worked, which didn’t, where they made judgment calls. One student wrote: “I felt most engaged when using AI for brainstorming, but struggled to trust the output’s accuracy.” That tension shows discernment! If you are concerned about authenticity in written reflections, consider brief presentations or self-recorded videos as alternatives.

3. Oral components

Finally, and already alluded to in my points above: oral components (whether brief videos or one-on-one discussions) support clarity, allow students to make mistakes and defend their thinking, and make superficial submissions much harder to sustain. The beauty is in the authenticity: you can’t fake genuine understanding in real-time conversation. I do admit, however, that including oral components may be difficult at scale, so delegation to smaller seminars or dedicated group sessions may be feasible ideas here.

Frameworks that actually help

Two frameworks helped me structure this shift systematically, moving from chaos to clarity:

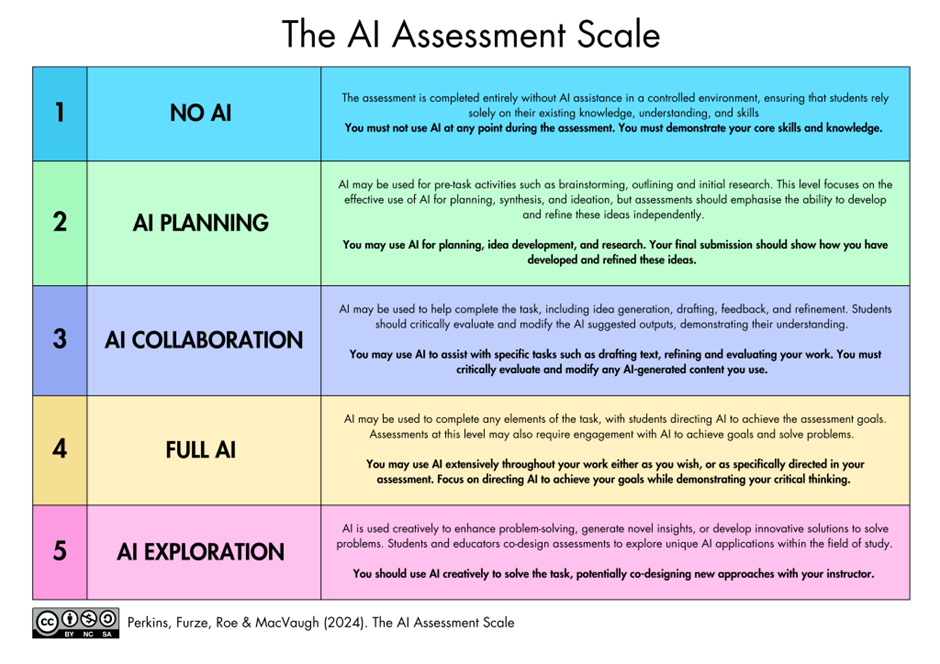

The AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) defines clear categories of acceptable AI use, from AI-prohibited to AI-assisted or AI-generated. It helps provide much-needed guidance to educators and students, as well as coherence across assessments. No more guessing games.

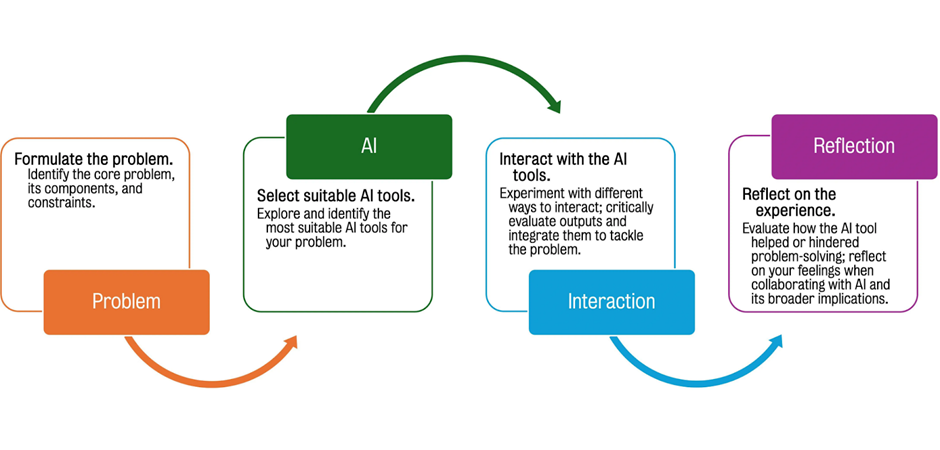

The PAIR framework from King’s College London (Problem, AI, Interaction, Reflection) encourages students to centre the problem or task first, then approach AI not as a shortcut, but as a tool to explore, iterate with, and ultimately reflect upon. It’s applicable in both assessment design and teaching activities.

Read more on the PAIR framework here

These frameworks helped me move from ambiguity to purpose, from reacting to AI to designing with (or without) it deliberately and rooted in pedagogical thinking, not emotional reaction. Explore them.

Creating inclusive learning spaces

My assessment structure (process and product) supports a more inclusive classroom in ways I hadn’t initially anticipated. Students with varied learning histories, language backgrounds, or neurodiverse profiles benefit enormously from tasks that reward transparency and self-awareness, not just polished grammar (unless that’s specifically a learning objective).

Some assessments include flexible elements where students select case studies based on local businesses or career pathways they’re genuinely interested in. Within these scaffolds, we can create meaningful spaces for student choice and agency. It’s not co-creation in its purest form, but it’s a significant step toward it.

Don’t forget the bigger picture

You might think I’m suggesting we abandon traditional assessments entirely. No! The key is understanding what each assessment method does best. Traditional essays still have their place, but now we need to be much more deliberate about when and why we use them.

AI isn’t going away, and neither is our responsibility to help students learn when and when not to use AI, basing their decisions on critical thinking, their own (professional) judgement, and – eventually – experience. And if they use it, doing so responsibly, ethically, compliant with law (e.g., GDPR), and with accountability.

Concluding thoughts

Let me be clear: ‘rethinking thine assessment’ is not trivial and requires a lot of time, commitment, institutional training, and skills development. But like Rome wasn’t built in a day, neither are ‘perfect’ AI-aware assessments (which may never be). We – students and educators – need to claim the space and time to try, learn what works and what doesn’t, and adapt, together.

Deciding pedagogically if and how to integrate AI into our assessment practices (and be transparent about it) will benefit our students and their learning experiences beyond any individual module or programme. I do not advocate that AI has to be included at all costs, but that educators become able to determine if – and how – AI may provide value without threatening student learning.

So: how are you rethinking assessment in your context? With or without AI? What tensions are you encountering as you steer this ‘sea change’? The conversation is ongoing, and I’d love to hear your experiences and insights.

References

Acar, O.A. (2023). Are Your Students Ready for AI? A 4-Step Framework to Prepare Learners for a ChatGPT World. Harvard Business Publishing Education. Available at: https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/are-your-students-ready-for-ai? (accessed July 15, 2025)

Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., and Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148

Dawson, P., Bearman, M., Dollinger, M., & Boud, D. (2024). Validity matters more than cheating. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(7), 1005–1016. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2024.2386662

Mayer, H., Yee, L.,Chui, M., and Roberts, R. (2025). Superagency in the Workplace – Empowering people to unlock AI’s full potential. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/superagency-in-the-workplace-empowering-people-to-unlock-ais-full-potential-at-work#/ (accessed August 21, 2025).

Perkins, M., Furze, L., Roe, J., and MacVaugh, J. (2024). The Artificial Intelligence Assessment Scale (AIAS): A Framework for Ethical Integration of Generative AI in Educational Assessment. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(06). doi:10.53761/q3azde36 Perkins, M., Roe, J., Vu, B.H., Postma, D., Hickerson, D., McGaughran, J., and Khuat, H.Q. (2024). GenAI Detection Tools, Adversarial Techniques and Implications for Inclusivity in Higher Education. arXiv Computers and Society. doi: 10.1186/s41239-024-00487-w

Dr Gerhard Kristandl is an Associate Professor of Accounting and Technology-Enhanced Learning at the University of Greenwich and a National Teaching Fellow. A recognised leader in Generative AI in higher education, he is a sought-after speaker and workshop facilitator in the field, both nationally and internationally.

At Greenwich, Gerhard has driven institution-wide innovation in technology-enhanced learning, embedding interactive tools, hybrid teaching methods, and AI-supported approaches into curriculum and assessment. His role as Mentimeter Lead has supported large-scale adoption of active learning strategies, while his leadership in initiatives such as “Women in Tech” reflects a commitment to inclusivity and diversity in digital education. Through his YouTube channel DrGeeKay | Educator Tech and active engagement across professional networks, Gerhard shares practical insights into Generative AI and digital pedagogy with educators worldwide. His work continues to shape assessment and learning practices, preparing students and colleagues for the opportunities and challenges of AI in higher education.

Email: g.kristandl@greenwich.ac.uk

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/drkristandl.bsky.social

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/gerhardkristandl