Lucien von Schomberg

When I started my academic journey in continental philosophy, I never imagined that one day I’d be designing a spinning cube to help people think ethically. But that’s exactly what the ethixCube™ has become: an ethics game that helps students and professionals explore moral dilemmas in a collaborative, practical way.

What sparked the idea?

The ethixCube™ was developed at Greenwich Business School, but its roots go back to my time as a PhD researcher and lecturer in philosophy at Wageningen University & Research. At Wageningen, known for its strong life sciences focus, the challenge was to make philosophy relevant to students with little or no background in the subject. Together with Professor Marcel Verweij, then chair of the philosophy group, we designed an ethics board game as part of the MSc module Philosophy and Ethics of Management, Economics, and Consumer Behaviour.

The idea was simple. Students sat around a deck of cards, each presenting a real-world dilemma. These included questions such as whether an intern on their first day should report a manager making racist remarks, whether Meta should remove misleading content at the cost of restricting free speech, or whether a company should prioritise shareholder profit over sustainability measures that lower returns. Each card offered responses linked to a major ethical theory. A consequence-based (utilitarian) response considered which option would produce the greatest overall benefit (Gustafson, 2013). A duty-based (deontological) response asked what obligation or rule must be followed, regardless of outcome (Micewski & Troy, 2007). A character-based (virtue ethics) response focused on what a virtuous person would do to show traits like integrity, compassion, and courage (Fontrodona et al., 2013). The aim was not to win but to reason together, then reflect on which kind of thinking most often guided the group’s decisions.

Why a game?

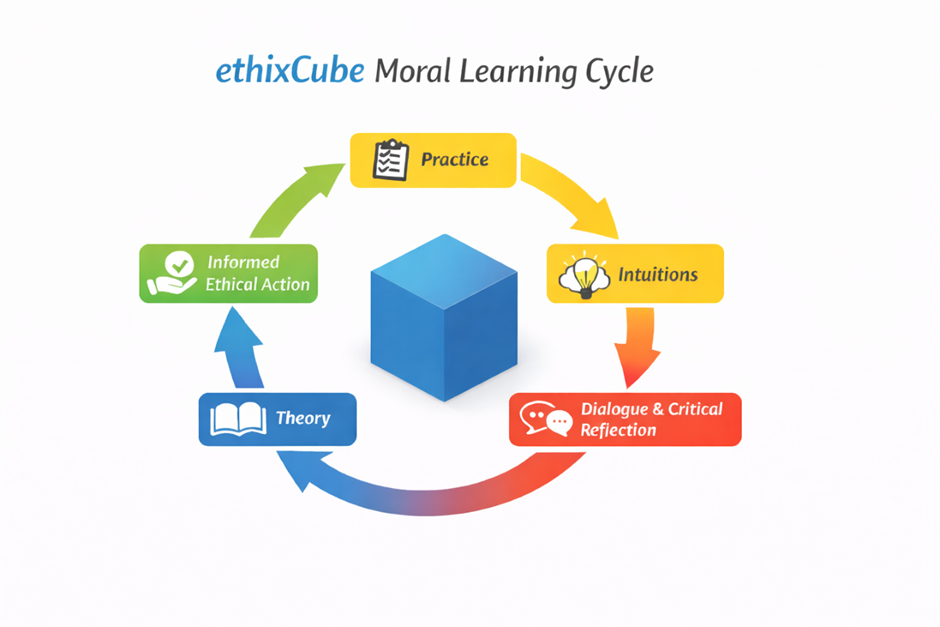

Traditional ethics education often starts with theory and moves to practice. For students new to ethics, this can feel abstract and alienating. This is where the ethixCube™ comes in. I developed a simple pedagogical model for moral learning to underpin it (Figure 1). It begins with practice, where students face concrete dilemmas. They then surface their intuitions about what feels right or wrong. Next, they reflect through dialogue with others, before linking their shared reasoning to ethical theory. This leads to informed ethical action, which then feeds back into practice.

Inspired by Paulo Freire’s (1970) critique of the “banking model” of education and supported by research on game-based learning (Krath et al., 2021; Staines et al., 2019), this approach flips the usual order. It treats ethics as something students do, not something they receive. This matters because people often comply with authority or group pressure, even when they sense something is wrong. We see this across sectors, where employees stay silent or follow instructions despite clear organisational wrongdoing (Wang et al., 2024). The ethixCube™ does not tell players what to think. It creates a bottom-up space where they test ideas, challenge each other, and build their own ethical position.

Reinventing the game

Fast forward a few years. I now teach a BA Business Ethics module at the Greenwich Business School to over 400 undergraduates across various programmes. I wanted to bring the game into this new context and push it further.

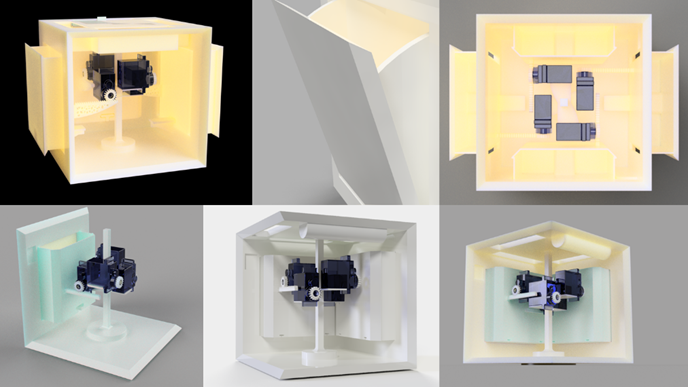

With funding from Scholarship Excellence in Business Education (SEBE), I partnered with the School of Design and then Head of School Anastasios Maragiannis to develop a more engaging, visually striking version. MA Digital Design alumnus Andreas Arany-Toth supported the project through his social enterprise, Design Dynamo. Andreas proposed turning the deck into a cube: something tactile and ‘spinnable’. Through Design Dynamo, he then brought in Surendrakumar Jayasuriyan, an MSc Product Design Engineering alumnus, who helped build the first prototype.

The shift from a flat board to a three-dimensional object opened new possibilities (Figure 2). Each face of the cube could represent a different theme, such as workplace ethics, sustainability, or technology. Players would spin the cube to land on a theme and then debate a dilemma linked to that topic. We also considered adding coloured tokens that pop out of the cube. Each token represents one of the three major ethical theories. As players choose their answers, they collect tokens that match the kind of reasoning they used. By the end of the game, the distribution of tokens reveals a personal “ethics profile”. A player might discover, for example, that most of their decisions were duty-based, with some guided by character and only a few by consequences. This mechanism not only makes the game more engaging but also gives players clear feedback on how they tend to think ethically.

Co-creating with students and professionals

To develop these ideas, we ran co-design workshops at the University of Greenwich and the University of Westminster. Participants included students, staff, and professionals from different sectors.

The workshops explored three questions: how should the cube look and feel, what dilemmas should it include, and how should it actually be played? Participants discussed everything from size and colour to the mechanics of play. Some suggested creating industry-specific versions. For example, a representative from J.P. Morgan proposed a finance edition. Someone working in a pharmaceutical company suggested a digital version that could be scaled globally, allowing colleagues in different offices to compare their ethical reasoning.

There were also ideas to keep the discussions more challenging. One participant suggested adding a “devil’s advocate” role to question the group’s reasoning and prevent easy agreement.

Deepening the content

While the cube format brought new energy, we also needed richer content. With funding from NUSC, and in collaboration with Dr Guodong Cheng, Dr Jiawei Li, and Dr Grace O’Rourke we hired two Research Assistants: Yash Thakur (BA Business Management) and Aarya Shirbhate (BSc Computer Science). Their brief was to create a structured database of real-world ethical dilemmas, clearly summarised in lay terms, supported with references (including articles and videos), and categorised by theme.

Each new case card now features a QR code linking to articles or videos for deeper context. We tested the expanded deck at another workshop at the University of Greenwich. Participants shared ideas not just for new dilemmas, but also for how the game could support organisational learning. They asked whether playing the game could reveal how a team or company tends to reason ethically, or whether it could be used in leadership development programmes. These discussions showed that the ethixCube™ has potential well beyond the classroom, offering organisations a way to reflect on their values and the decision-making cultures they cultivate.

Student-led knowledge exchange

The ethixCube™ now plays a structured role in my Business Ethics module assessment. In Week 2, students use the ethixCube™ to explore pre-designed ethical dilemmas. This early exposure helps them see how ethics plays out in practice and builds confidence in speaking and deliberating with peers. The tool returns in Week 8, when students bring their own self-created ethical cases to class. Creating a case for the ethixCube™ forms part of their assessment, and the Week 8 session allows students to test their cases with peers, receive feedback, refine their ethical framing, and improve the clarity and nuance of their final submissions. This creates a strong cycle of learning: students experience the cube as participants first, and later as designers and facilitators of ethical scenarios.

The ethixCube™ has also started to travel beyond my own teaching. Dr Guodong Chen integrated an adapted version of the tool into Ethical and Legal Aspects of Business Analytics. He extended the format by adding a “Twist card” introducing new complications and a two-stage deliberation structure. He used this across five tutorials with around 100 postgraduate students. His evaluation reported that over 90% of students found the activity engaging, with nearly 80% finding it very engaging. The ethixCube™ is also embedded in TNE delivery at our partner institutions in Vietnam and Malaysia, supporting pedagogical coherence across international contexts and reinforcing the tool’s adaptability.

This tool is further supported by a team of 46 ethixCube™ student ambassadors, who volunteer across research, facilitation, testing, and dissemination. This structure embeds knowledge exchange within the student experience and supports scalable development, while building graduate skills in ethics, facilitation, and responsible innovation.

Looking ahead: External funding and scaling

The ethixCube™ now forms the foundation of two externally funded projects I lead, extending its impact beyond the classroom.

- BRIDGE – Building Responsible and Inclusive Digitalisation through Game-Based Engagement was awarded €60,000 through REINFORCING (Horizon Europe cascading call). Starting in November 2025, BRIDGE works with the Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) and its network of 80+ organisations to address ethical dilemmas linked to AI, surveillance, and data governance in higher education. It combines institutional pilots with industry engagement and policy-facing dissemination, including an accepted special session at the Eu-SPRI conference (June 2026).

- GEPPIE – Game-based Ethics and Public Policy for Inclusive Education was awarded £23,996.24 by the British Council to establish a new Transnational Education partnership with the Federal University of Paraná (Brazil). Starting in January 2026, GEPPIE develops bilingual (EN–PT) ethics scenarios and teaching resources to support public policy education across the UK and Brazil.

The next phase is about building on this momentum. The ethixCube™ will keep developing through student-led adaptation, including digital and hybrid formats. BRIDGE will support institutional and sector-level approaches to responsible digitalisation. GEPPIE will strengthen ethics and public policy teaching across two regions. Further proposals are already in development to position the ethixCube™ as a leading ethics education tool across disciplines and professional contexts.

On a more speculative note, it would be fascinating to explore how augmented reality could bring the ethixCube™ to life. Imagine players wearing AR glasses, with ethical dilemmas projected into the room as immersive scenarios. An AI-powered facilitator could mediate discussion, offer prompts, or play devil’s advocate when group consensus becomes too comfortable. Perhaps not as far off as it sounds.

For now, the priority is simple: keep testing the cube in new contexts and keep building a community of users who can adapt it to their needs. The long-term vision is for the ethixCube™ to become a recognised resource for ethics education worldwide, making ethical reasoning accessible, engaging, and meaningful wherever people face difficult decisions.

References

Fontrodona, J., Sison, A. J. G., & De Bruin, B. (2013). Editorial introduction: Putting virtues into practice. A challenge for business and organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(4), 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1679-1

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum

Gustafson, A. (2013). In defense of a utilitarian business ethic. Business and Society Review, 118(3), 325–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12013

Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & Von Korflesch, H. F. O. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, 106963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106963

Micewski, E. R., & Troy, C. (2007). Business ethics – deontologically revisited. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9152-z

Staines, D., Formosa, P., & Ryan, M. (2019). Morality play: A model for developing games of moral expertise. Games and Culture, 14(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017729596

Wang, Z., Ren, S., Chadee, D., & Chen, Y. (2024). Employee ethical silence under exploitative leadership: The roles of work meaningfulness and moral potency. Journal of Business Ethics, 190(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05405-0

Dr Lucien von Schomberg is Senior Lecturer in Creativity and Innovation at the University of Greenwich and Academic Portfolio Lead for Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Sustainability. His research focusses on responsible innovation, the philosophy of technology, and business ethics. He has published in leading journals, presented at international conferences, and contributed to EU-funded consortia totalling €15 million. Lucien is founder of the ethixCube™ and Principal Investigator of BRIDGE (€60,000) and GEPPIE (£23,996.24), advancing game-based ethics across industry, higher education, and public policy. At Greenwich, Lucien teaches a large Business Ethics module (400+ students), also delivered at partner institutions in Vietnam and Malaysia. He led the design of a new BA Entrepreneurship and Innovation programme and won the Inspirational Teaching Award at the 2024 Student-Led Teaching Awards. Off campus, he is a playwright and actor with London-based theatre companies, and a UEFA-A licensed football coach with over ten years of experience at top European clubs.

Email: l.vonschomberg@greenwich.ac.uk

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lucien-von-schomberg-97b432134/

Personal website: www.lucienvonschomberg.com