by Richard Scott

Visiting Lecturer, Greenwich Maritime Institute and MD, Bulk Shipping Analysis

Africa’s profile as an exporter of dry bulk commodities is rising. Responding to growing import demand from China, India and other buyers in the past decade, many new African suppliers have entered the market. Seaborne dry bulk exports by countries in Africa now exceed 200 million tonnes annually, about 5% of the global total, and further growth is predicted over the years ahead. Expansion has been especially notable in the iron ore and coal trades, the focus of this article.

Seaborne exports growth from Africa benefits the global shipping industry in two ways. Larger volumes moving create additional employment for bulk carriers, many of which are operated by independent shipowners. Also, because a large element of new commodity supply is coming out of West Africa, destined for Asian receivers, long-haul voyages amplify the extra cargo-carrying (deadweight) capacity needed.

There is a remarkable historical precedent. Around fifty years ago, back in the 1960s, Africa rapidly became much more significant as an exporter when iron ore deposits were opened up in several West African countries, mainly to supply the European market. This trade subsequently diminished and was overtaken by the emergence and eventual dominance of South Africa as the continent’s chief iron ore and coal exporter. The current phase starting in the past few years represents, partly, a reprise of earlier events in West Africa, accompanied by some new developments elsewhere.

A steely embrace

For most of the past ten years coal, from South Africa, was the largest dry bulk cargo export movement originating in the African continent. But in 2013 Africa’s iron ore exports, which had been rising, especially in the five years since 2008, became the largest element. Estimates point to last year’s iron ore total reaching about 91mt. South Africa’s contribution comprised more than three-fifths. The remainder consisted mainly of shipments from Mauritania plus the rapidly expanding resumed exports from Sierra Leone and Liberia.

A large proportion of iron ore exports growth reflected China’s expanding requirements amid rapid steel production increases. During the five years period from 2009 to 2013, Africa’s annual ore exports total increased by 49mt. In the same period African cargoes transported annually to China rose by over 48mt, based on official Chinese import figures. This relationship clearly demonstrates the significance of China for the development of African trade. Although South Africa was the main origin of iron ore purchases by Chinese buyers, supplying 43mt last year, increasing volumes were bought from Mauritania, reaching 9mt in 2013. During last year and the preceding year, Sierra Leone became a much more important supplier to China, with the annual quantity surging to 12mt in 2013. Smaller volumes in the past twelve months were derived from Liberia (just over 1mt) plus a minor 0.2mt from Guinea.

Iron ore exports from South Africa more than doubled in the past ten years. From 23mt in 2003, the total rose to 58mt in 2013. The largest part of this growth occurred within the past five years, reflecting greatly increased volumes purchased by Chinese buyers. Ore deposits are mainly located in the Northern Cape Province, where Kumba Resources’ Sishen mine is by far the biggest. This mining area is linked by a railway, 860 kilometres in length, to Saldanha Bay port north-west of Cape Town, which has a terminal (operating since the mid-1970s), designed for capesize bulk carriers.

The ramping up of iron ore exports from West Africa within the past few years is particularly noteworthy. Mauritania’s shipments showed gradual growth over the past decade. Liberia and Sierra Leone, by contrast, remained absent from the international market until 2011 when they both resumed participation on a minimal scale; then there was a rapid building up of sales over the next two years.

In Mauritania, sales historically were focused on Europe’s steel industry, involving a relatively short-haul sea voyage implying lower transport costs compared with more distant sources. Since the mid-2000s a changing emphasis towards Asian markets resulted in the share of long-haul shipments from Mauritania growing. Although the total exported by state-owned iron ore miner SNIM increased only slowly to 13mt in 2013, volumes shipped to China rose very strongly, resulting in China becoming by far the largest customer. This growth was assisted by Nouadhibou port’s recently enlarged ability to load capesize bulk carriers (typically 180,000 deadweight tonnes capacity), often the most economical vessel size for ore trades.

Liberia’s iron ore production ceased during the civil conflict, which persisted from 1989 for fourteen years. In September 2011 global steel producer ArcelorMittal restarted ore exports, when a 63,000 tons panamax size shipment was loaded at Buchanan port. As volumes from the Yekepa, Nimba mine rose, an offshore loading facility for capesize bulk carriers was subsequently introduced. Then, at the beginning of this year, shipments resumed from the long-closed Bong mine. New operators China Union (part of Wuhan Iron & Steel), a majority shareholder in Bong, plan to move 50,000 tonnes monthly through 2014 to China from a new pier at the port of Monrovia.

Also in this mineral-rich corner of West Africa, Sierra Leone’s iron ore mining has come back to life vigorously. A 50,900 deadweight bulk carrier departed from the port of Pepel in November 2011 carrying an ore cargo, reinstating another long-defunct operation. Mining company African Minerals has installed a capesize transshipment facility at Pepel to serve its Tonkolili mine. Another mining company, London Mining, began exporting from its Marampa mine in 2012, utilising river barge movements and a transshipment operation at the port of Freetown.

A curious venture

All these three West African countries – Mauritania, Liberia and Sierra Leone – have plans to greatly expand iron ore production and exports over the next few years at least. Another project, regularly making newspaper headlines, is the plans to develop a vast iron ore deposit contained within the Simandou mountain range of Guinea. This project, which could eventually yield up to 100mt of high-quality ore annually for foreign markets, has seen controversial ownership changes. One prominent problem for the developers is the proposed mine’s remote location, requiring construction of a 650 kilometer railroad through difficult terrain to the port of Conakry. The total cost has been variously estimated at $18-20 billion, including mine infrastructure, building a new railway, plus developing the port to handle large ships.

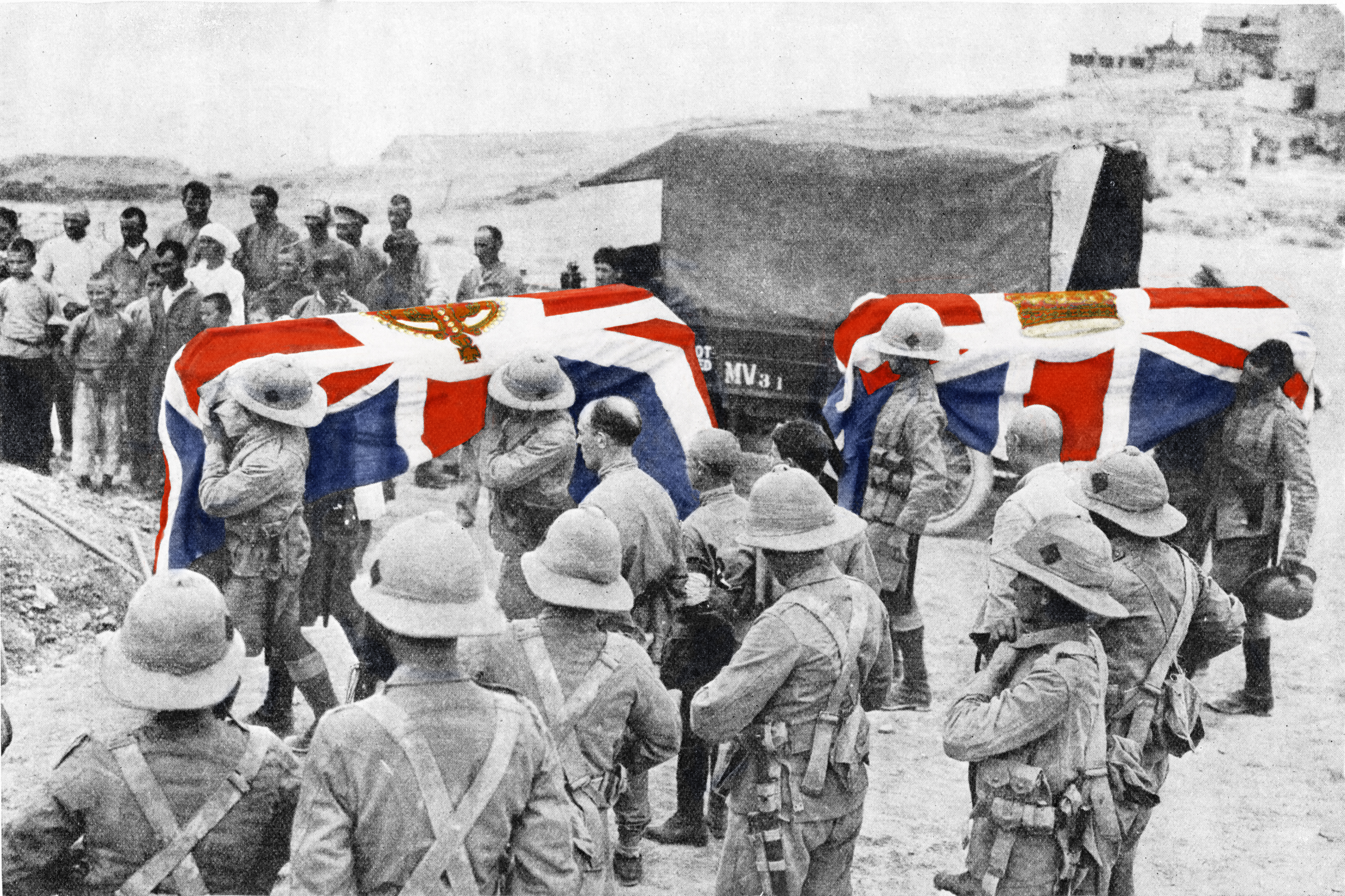

The renewed prominence of the name Simandou resonates with events about fifty years ago. During the early 1960s, iron ore was being produced in Guinea at a deposit about five miles from Conakry and exported to Europe, mainly to the United Kingdom. The Guinean government decided to purchase a new bulk carrier, intending to employ it in the ore trade from Guinea to the UK. This story is told by Iain Harrison, founder and chairman of shipowners and managers Harrisons (Clyde) Ltd, in his fascinating history of the family company, entitled ‘A Curious Venture’. A bulk carrier of 15,000 deadweight tons named ‘Simandou’ was ordered from shipbuilders Scotts of Greenock and delivered in 1963. Harrisons arranged the deal and were appointed managers. But a long term contract for employment in the intended iron ore trade proved unobtainable, and so the ship was used in open market dry cargo trades around the world.

A generation game

Africa’s coal exports scene has been dominated by South Africa. But the South African trend over the past ten years was fairly flat, as various influences restrained sales despite robustly growing global import demand. Supplies from South Africa mainly comprise steam coal, chiefly used in electricity generation. A small proportion, less than 2 percent, of exports is coking coal used by the steel industry. After totalling 71mt in 2003, there was a dip in the 2008 and 2009 period down to 63mt annually, before a recovery to 74mt in 2013. During this period, emphasis switched away from European destinations towards faster growing Asian markets, especially India, and also China.

Although South Africa is ideally situated to supply both Atlantic and Pacific markets, this advantage was not exploited to maximum benefit in recent years. Most coalfields are located in the country’s north east, and are linked by rail to the principal coal loading port of Richards Bay, on the east coast north of Durban. This port has been expanded greatly to enable huge volumes to be handled, theoretically now 91mt annually, but the higher capacity remains under-utilised. Lack of strong growth has been attributed to inadequate rail transport connections with the coalfields, and also to insufficient mining capacity, together restricting sales.

While South Africa’s coal exports are much larger in volume than exports from other African countries, developments elsewhere in the past few years have often attracted a far greater degree of interest. This characteristic particularly applies to Mozambique, where the challenges for producer exporters could be described as tough, similar to those faced by some new iron ore shippers in West Africa. Mozambique, and also Botswana, possess huge deposits of good quality coal, but developing the infrastructure (railroads and ports) required to enable access to international markets is a hugely expensive and lengthy process.

Coal mines in the Tete province of Mozambique, where coking as well as steam coal grades are available, started exporting small quantities in 2011, leading to more substantial exports of about 3mt in 2012. Brazilian mining company Vale started producing at the Moatize mine in 2011, transporting coal along the 575 kilometre Sena railway to Beira port. Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto began producing at the Benga mine in 2012. Last year, a further increase in the country’s exports, reportedly to about 5mt, was seen.

Expanding the capacity of the existing rail route, and building a new route, will enable more coal to be exported from Mozambique. The Sena railway is being upgraded from a maximum 6.5mt annually to 20mt, and the handling capacity at Beira is being raised. A new 912 kilometre line carrying coal through Malawi to a new deepwater loading port at Nacala in northern Mozambique is due for completion at the end of 2014, with potential for carrying up to 18mt exports.

Problems associated with developing mineral resources for export were highlighted by a news item at the end of July this year. The Financial Times reported that Rio Tinto had finalised the sale of its Benga coal mine and other Mozambique coal assets, to an Indian state-owned company, for $50 million. This price tag is only a small fraction of the $3.7 billion originally paid by Rio Tinto in 2011 for the Riversdale company owning these assets, described by the FT as a “disastrous acquisition.” The logistical challenges of transporting coal from Tete to the coast, and a reduced estimate of recoverable coking coal volumes had been identified earlier as key problems, amplified later by the adverse impact of sharply lower international prices.

Maritime momentum

Looking at how the sea trade scene as a whole has been evolving, the pull of increasing demand from Asian markets, in particular China and India clearly has been a crucial factor stimulating and underpinning Africa’s dry bulk commodity exports growth. Assuming that this influence remains favourable over the years ahead, further expansion in a number of trades seems predictable although timescales and volumes are harder to estimate precisely. Large-scale iron ore and coal mining projects are under way in several countries already, as we have seen, and more are planned, together with related infrastructure developments, aimed at expanding foreign sales.

The sheer magnitude of the task of organising minerals movements, from inland locations to coastal loading ports, for onwards sea transportation to foreign markets, has sometimes been daunting. For several projects the costs are proving almost prohibitive. This problem is, of course, related to commodity prices obtainable on the world market. If prices are high enough, projects with even excessive costs can prove profitable. But recently iron ore and coal prices have fallen steeply from peak levels as huge additional relatively low-cost supplies become available around the world, resulting in greater challenges for some developing African projects.

International seaborne movements of dry bulk cargoes originating in African countries are not entirely confined to iron ore and coal. These two commodities have seen probably the most impressive developments and export growth in the past decade, but others are significant. Among minerals, bauxite and its processed form alumina, especially from Guinea is a key element, while phosphates from Morocco is another prominent example. Altogether, annual mineral exports by sea from Africa have grown by about 50 percent during the past ten years, to an estimated total now exceeding 200mt, as mentioned earlier. This expansion has raised the continent’s status in the global shipping market. It has been reflected in the much higher deadweight volume of bulk carriers employed in trades, many involving long-haul routes, beginning in ports in West African and southern African countries.